November 17, 2017

It’s unrealistic to expect MPs to follow the view of the people who elected them every time

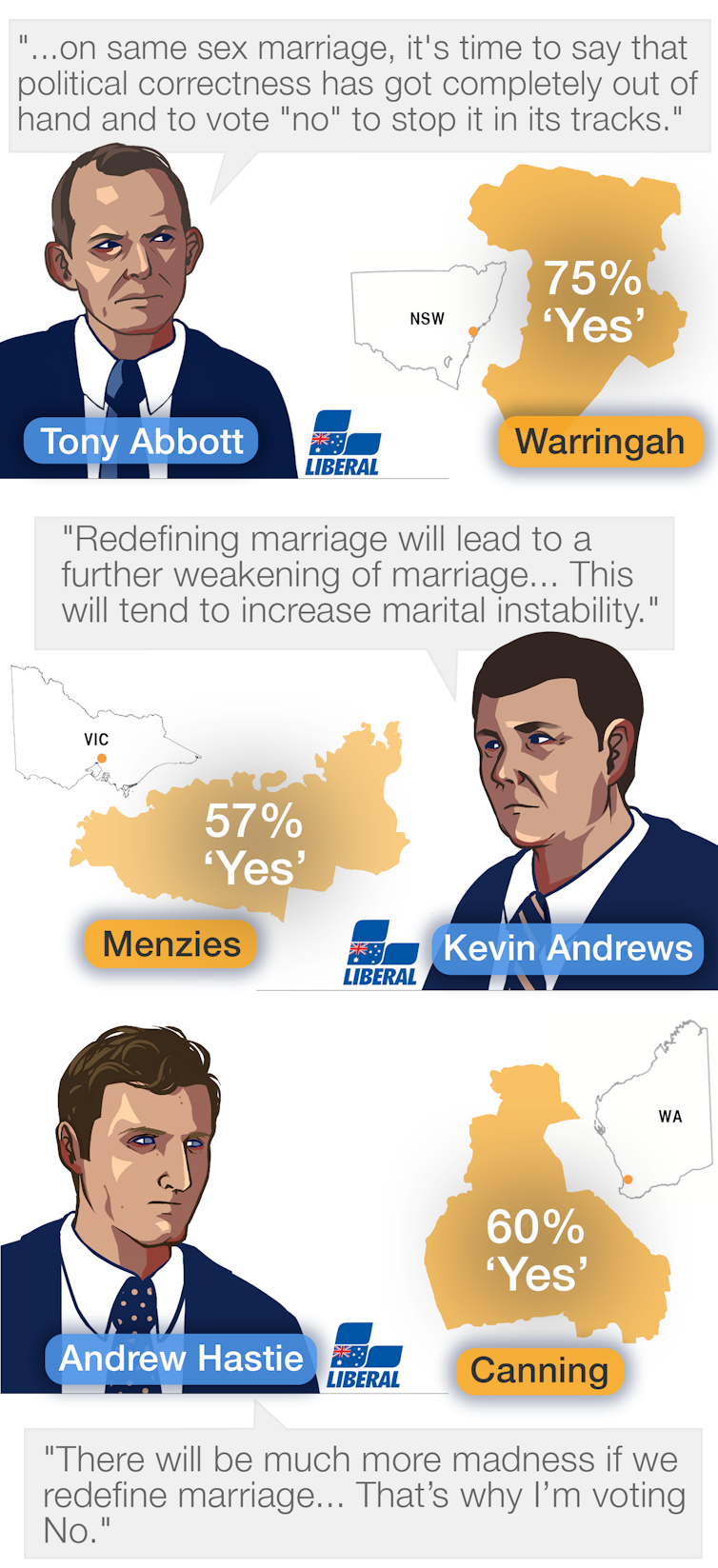

The same-sex marriage survey results showed up which members of parliament voted in a starkly opposite fashion to those in their electorates.

Gregory Melleuish, University of Wollongong

The electorate of Blaxland had a strong “no” vote, while their MP Jason Clare voted yes, and in prominent “no” campaigner Tony Abbott’s seat of Warringah there was a strong “yes” vote.

Some people may think it’s the duty of their MP to vote in the way they did. Of course, this could mean that as every state voted “yes” then the Senate as a whole should support the same-sex marriage legislation. But generally, this connection between popular sentiment and how a MP votes is usually made in terms of single member constituencies.

It’s based on a very old idea of the role of MPs as “delegates” or “agents” of their constituents and therefore liable to be issued instructions on how they should vote on any issue. This idea relates back to a time when parliament, especially in England, could be understood, as bringing together the interests of its various boroughs and counties.

This model of representation is difficult to sustain once a country is understood as constituting a national entity with a unified political culture. It’s also difficult to sustain once parliament begins to deal with a range of complex policy matters.

The idea of a newly elected member being issued with a list of instructions and then needing to go back to their constituents every time a new issue arises may sound very democratic, but it’s also quite impractical.

In the eighteenth century a new model of representation arose which is known as the trustee model. It was given its most famous expression by the English politician Edmund Burke, who argued that representatives were elected not just to represent their local constituency but also the nation as a whole. They were not agents but trustees. They could not be instructed by their constituents but instead would use their personal judgement and conscience as the basis of their decision on any particular policy matter.

The idea of the member as a trustee was very popular in colonial Australia, at least in theory, but it did not prevent colonial parliaments being full of what are termed “roads and bridges” members who worked hard to win benefits for their local areas. A lack of instructions does not mean that a member will cease to work for the material improvement of their constituencies.

Nevertheless, the delegate model of representation had strong support in Australia, particularly from radicals. David Syme, owner of The Age newspaper, was a big supporter. The early Labor Party equally was structured around the model such that Labor MPs were ultimately responsible to the party conference.

Vere Gordon Childe in How Labour Governs has chronicled how this system worked and, I believe, how it created all sorts of problems for the party. Childe demonstrated that those who seek to control MPs are also often those who are seeking to replace them.

The idea of the member as delegate is generally advocated because it’s seen as being an expression of true democracy. The problem is that it posits an idea that the average citizen takes a very active interest in politics and wants to have a say.

The opposite view is that most people have little interest in politics and having elected a member it’s the role of the member to “do politics”. This means that they also expect their member to intervene on their behalf when assistance is required.

In his wonderful 1970 movie The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer, the late and great Peter Cook provided a picture of how a combination of marketing techniques and a desire to make a country more “democratic” could lead to the opposite effect.

In the movie the citizens of Britain, bombarded with referenda on every trivial policy issue, are finally asked to turn all power over to Rimmer to which, in a state of exhaustion, they vote “yes”.

There is a very real danger in the ideal of the member as delegate, and in the notion that the member is there to do the bidding of their constituents. Imagine if every time an issue was to be determined every electorate was polled as to their views on the matter, as happens in Cook’s movie.

It would not last. In the same-sex marriage case it has been a novelty but the novelty would soon wear off.

Moreover, the major people to benefit from such a situation would be those political activists who believe their voices are not being heard and, following Childe, who wish to replace those who are currently MPs.

In reality, we have a mixed model of representation which does bind not members to the instructions of their constituents, but which also recognises that a local member should work hard on behalf of those whom they have been elected to represent.

![]() Reality is always messy and escapes attempts to boil it down into models. Members represent both the nation and their local electorate and must find a way to balance the two.

Reality is always messy and escapes attempts to boil it down into models. Members represent both the nation and their local electorate and must find a way to balance the two.

Gregory Melleuish, Professor, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/live-migration/www/images/content/groups/public/web/media/documents/mm/uow241069.jpg)