December 11, 2017

No, most people aren’t in severe pain when they die

Many people fear death partly because of the perception they might suffer increasing pain and other awful symptoms the nearer it gets.

Kathy Eagar, University of Wollongong; Sabina Clapham, University of Wollongong, and Samuel Allingham, University of Wollongong

There’s often the belief palliative care may not alleviate such pain, leaving many people to die excruciating deaths.

But an excruciating death is extremely rare. The evidence about palliative care is that pain and other symptoms, such as fatigue, insomnia and breathing issues, actually improve as people move closer to death. More than 85% of palliative care patients have no severe symptoms by the time they die.

Evidence from the Australian Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC) shows that there has been a statistically significant improvement over the last decade in pain and other end-of-life symptoms. Several factors linked to more effective palliative care are responsible.

Read more: What is palliative care? A patient’s journey through the system

These include more thorough assessments of patient needs, better medications and improved multidisciplinary care (not just doctors and nurses but also allied health workers such as therapists, counsellors and spiritual support).

But not everyone receives the same standard of clinical care at the end of life. Each year in Australia, about 160,000 people die and we estimate 100,000 of these deaths are predictable. Yet, the PCOC estimates only about 40,000 people receive specialist palliative care per year.

Symptoms at the end of life

For the greater majority of those who do receive palliative care, the evidence shows it is highly effective.

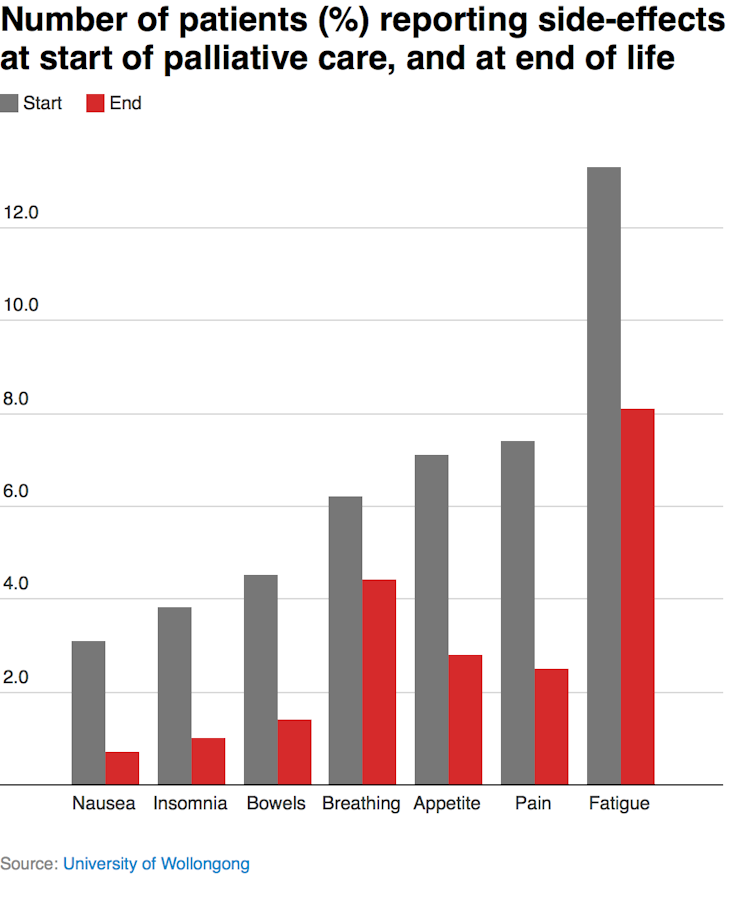

The most common symptom that causes people distress towards the end of life is fatigue. In 2016, 13.3% of patients reported feeling severe distress due to fatigue at the start of their palliative care. This was followed by pain (7.4%) and appetite (7.1%) problems.

Distress from fatigue and appetite is not surprising as a loss of energy and appetite is common as death approaches, while most pain can be effectively managed. Other problems such as breathing, insomnia, nausea and bowel issues are experienced less often and typically improve as death approaches.

Contrary to popular perceptions, people in their final days and hours experience less pain and other problems than earlier in their illness. In 2016, about a quarter of all palliative care patients (26%) reported having one or more severe symptoms when they started palliative care. This decreased to 13.9% as death approached.

The most common problem at the start was fatigue, which remained the most common problem at the end. Pain is much less common than fatigue. In total, 7.4% of patients reported severe pain at the beginning of their palliative care and only 2.5% reported severe pain in the last few days. Breathing difficulties cause more distress than pain in the final days of life.

These figures must be considered in relation to a person’s wishes. It’s true for a small number of patients that existing medications and other interventions do not adequately relieve pain and other symptoms.

But some patients who report problematic pain and symptoms elect to have little or no pain relief. This might be because of family, personal or religious reasons. For some patients, this includes a fear opioids (the active ingredient in drugs like codeine) and sedating medications will shorten their life. For others, being as alert as possible at the point of death is essential for spiritual reasons.

Not everyone gets this care

Patient outcomes vary depending on a range of factors such as the resources available and geographical location. People living in areas of high socioeconomic status have better access to palliative care than those who live in lower socioeconomic areas.

The PCOC data demonstrate those receiving care in a hospital with dedicated specialist palliative care services have better pain and symptom control (due to the availability of 24-hour care) compared to those receiving palliative care at home. There is now a national consensus statement to improve the provision of palliative care in hospitals. This needs to be extended to include death at home and death in residential care.

Although there are national palliative care standards and national safety and quality standards, each state, territory, health district and organisation is responsible for the individual delivery of palliative care. Subsequently, differing approaches to delivery and resources exist in the provision of palliative care.

Recent reports by the New South Wales and Victorian Auditor-General Offices highlight the demand for palliative care services and the need for appropriate resourcing to support patients, carers and families as well as for more integrated information and service delivery across care settings.

Australia can do better

The Australian Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration holds information on more than 250,000 people who have received specialist palliative care over the last decade. Although participation in the data collection is voluntary, there has been steady uptake. The collaboration estimates that information on more than 80% of specialist palliative care patients is being reported each year.

Australia is in a unique position internationally as it has a national system to routinely measure the outcomes and experience of palliative care patients and their families. These data can help clinicians to measure the effectiveness of their care and help providers adopt best practice. This information is also critical evidence that can be used to inform public debate.

![]() The evidence is Australian palliative care is effective for almost everyone who receives it. But the problem is that many thousands of people die each year without access to the specialist palliative care they need. As a country, we need to do better.

The evidence is Australian palliative care is effective for almost everyone who receives it. But the problem is that many thousands of people die each year without access to the specialist palliative care they need. As a country, we need to do better.

Kathy Eagar, Professor and Director at Australian Health Services Research Institute University of Wollongong, University of Wollongong; Sabina Clapham, Research fellow, Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration, University of Wollongong, and Samuel Allingham, Research Fellow, Applied Statistics, University of Wollongong

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/live-migration/www/images/content/groups/public/web/media/documents/mm/uow241364.jpg)