May 10, 2017

Primitive cousin Homo naledi much younger than thought

Dating of fossils shows the species co-existed with modern humans

Efforts to date Homo naledi fossils have produced an unexpected result; the early human species lived much more recently than scientists had thought.

Homo naledi fossils were discovered in the Rising Star cave system in South Africa in 2013. While the fossils shared some anatomical features with modern humans (such as the shape of their wrist bones), other features (such as the small size of the skull) had more in common with some of the earliest members of the Homo genus, Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis, who lived close to two million years ago.

While the mix of primitive and modern features made it hard to place in the evolutionary timeline, the most common theory was that Homo naledi probably lived perhaps one to two million years ago.

However, a large international team of researchers has now dated those fossils, and the results show that Homo naledi was most likely alive sometime between 236,000 and 335,000 years ago. The finding means Homo naledi was alive at the same time as Homo sapiens – modern humans – first appeared.

Associate Professor Anthony Dosseto from the University of Wollongong’s (UOW) School of Earth and Environmental Sciences was part of the team that dated the fossils and is a co-author of the paper “The age of Homo naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa” published in the academic journal eLife on 10 May 2017. The paper’s lead author is Professor Paul Dirks from James Cook University.

Professor Dosseto said the results of the dating were “completely” unexpected.

“The thing with Homo naledi, the structure of the individual, it’s very primitive looking,” he said.

“Before there was any dating people thought it probably lived around two to one million years ago. This type of hominin was thought to be completely extinct by 200,000 years ago when you start seeing in Africa modern humans. “So it was a big surprise to see Homo naledi around the time you start to have modern humans kicking around in Africa.”

Left: The skull of an archaic human next to the ''Neo'' skull of Homo naledi. Right: "Neo" skeleton of Homo naledi. Photos: Wits University/John Hawks

Left: The skull of an archaic human next to the ''Neo'' skull of Homo naledi. Right: "Neo" skeleton of Homo naledi. Photos: Wits University/John Hawks

To ensure their dating results were robust, the researchers used several different methods, including uranium-series dating and electron spin resonance dating (ESR), with several different labs independently dating the same samples using the same techniques. This was done without one lab knowing the results from the other labs.

One of the labs that did this testing was the Wollongong Isotope Geochronology Lab at UOW.

“What we’ve been doing is directly dating some of the remains, the teeth, of the Homo naledi,” Professor Dosseto said. “There’s different ways you can date archaeological sites, but at the end of the day it’s best when you’re trying to figure the age of an individual to be able to date that individual directly.

“What I’ve been involved with was the uranium-series analysis, which is needed to be able to do ESR dating. It was sort of a blind date, if you like, with Homo naledi samples sent to different labs so the people leading the project could see if we would get consistent ages on the same samples - and we did.”

Professor Dosseto said it was exciting to work on a project that could change our understanding of human evolution.

“Being involved with the dating, it’s an amazing feeling when you crunch the numbers with your colleagues, derive an age for the individuals and you grasp the significance of these ages for human evolution,” he said.

“Over the past five or 10 years our understanding of human evolution has been completely blown away. We thought human evolution was much more linear than we now realise. We now know that different types of Homo, like the hobbit, may have coexisted with Homo sapiens.

"And we’ve been seeing, over the years, that the University of Wollongong has been quite central to these sorts of discovery.

“It’s really fascinating. It’s the irony of archaeology, where you’re looking at dead things, things from the past, but it’s very dynamic at the moment. Of all this fields I’m working in, it’s one of the most dynamic.”

The facility used at UOW in this project was funded by an ARC LIEF grant.

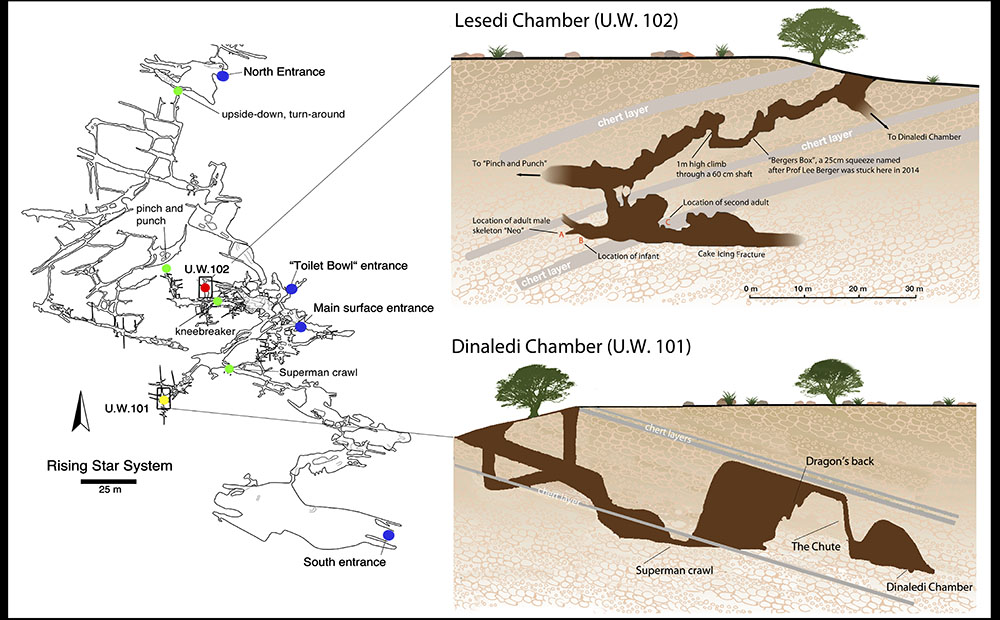

Schematic of the Rising Star cave system where the Homo naledi bones were found. Picture: Marina Elliott/Wits University

Schematic of the Rising Star cave system where the Homo naledi bones were found. Picture: Marina Elliott/Wits University

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/live-migration/www/images/content/groups/public/web/media/documents/mm/uow232125.jpg)