December 8, 2017

Sustainable shopping: how to buy tuna without biting a chunk out of the oceans

Shopping can be confusing at the best of times, and trying to find environmentally friendly options makes it even more difficult. Welcome to our Sustainable Shopping series, in which we ask experts to provide easy eco-friendly guides to purchases big and small.

Candice Visser, University of Wollongong and Quentin Hanich, University of Wollongong

Tuna is the most popular canned fish eaten in Australia and one of the most popular fish produced worldwide. The total catch of tuna in 2013 was about 7.4 million tonnes.

Tuna is a massive industry and most of this catch ends up in cans. But while each can of tuna might look similar, the environmental impacts of different brands vary. So, with a sea of “eco-friendly” labels and choices, how do you know which is the most sustainable?

Read more: Australian endangered species – Southern Bluefin Tuna

Almost all Australian canned tuna is imported

Australia produces large amounts of high-end seafood such as rock lobster, abalone and fresh tuna, but most of this doesn’t end up in our supermarkets – it is exported to countries willing to pay more. Instead, roughly 70% of all seafood eaten in Australia is imported. Most of this includes lower-value products such as frozen fish, frozen prawns and canned tuna.

Australia is a major market for canned tuna. Almost all of the canned tuna sold here comes from Thailand, which processes about half of the world’s tuna supply. It is now almost impossible to buy Australian-produced canned tuna since large-scale production in Australia ended in May 2010.

While it is not unusual for a developed country to import large amounts of seafood, Australia is failing to meet international standards for sustainable seafood trade. Australia has strict requirements for seafood exports, but seafood imports are largely unregulated. This means it can be difficult to know if the imported seafood you buy was caught sustainably or even legally.

Catching 7.4 million tonnes of tuna

High global demand drives unsustainable fishing practices. These practices include overfishing, issues related to bycatch (which is the accidental catch of other marine animals like dolphins, turtles and seabirds), and “illegal, unregulated and unreported” (IUU) fishing. Now, 77% of the world’s fisheries are fished at their limit or beyond.

Unsustainable fishing practices have devastating effects on the health of the marine ecosystem and the livelihoods of fishers. With this in mind, it is more important than ever to know about the origin of your fish.

Some species of tuna are fished at sustainable rates, whereas others are overfished. The most common species that end up in cans are skipjack and yellowfin tuna. Both of these species have sustainable stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO). Skipjack also has sustainable stocks in the Indian Ocean. Higher-value species such as bigeye and bluefin varieties are usually reserved for sushi and sashimi markets. Southern bluefin tuna is overfished and is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN.

Read more: Australian endangered species: southern bluefin tuna

The type of catch matters

The most sustainable fishing methods for tuna are “pole-and-line” and “FAD-free purse seine”. However, each method has a catch.

Pole-and-line fishing is the traditional method of using a pole, line and hook to catch fish. The rate of bycatch is small because fishers can catch and release non-tuna species. However, bait fish are used to attract the tuna, which can have a large impact if the bait fish is not caught in a sustainable way. Due to the labour-intensive nature of pole-and-line fishing and dependence on bait fish, this method makes up only a small proportion of the total tuna caught and is unable to supply tuna in large amounts.

Purse seine fisheries use a large net to surround a school of fish. In recent years purse seiners have increasingly used fish aggregating devices (FAD) to attract tuna and increase their efficiency. However, FADs also attract bycatch and juvenile tuna and are poorly regulated. Therefore, only purse seine fisheries that set on free-swimming schools of tuna are considered sustainable.

Quick guide to better tuna

What can you do?

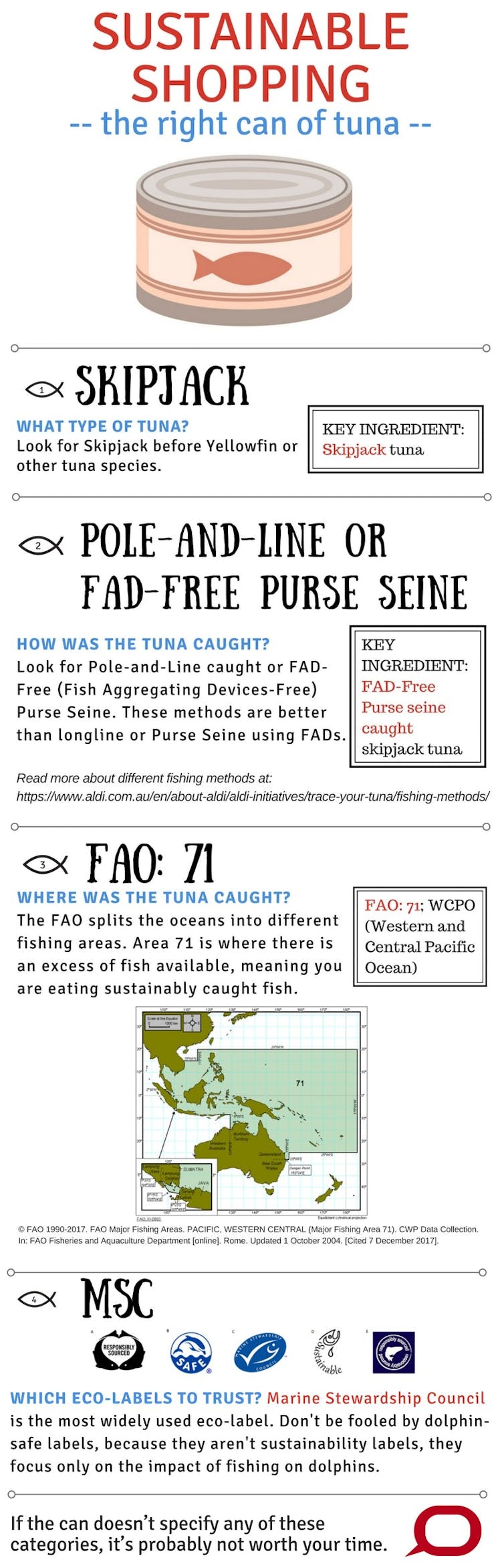

1. Read the label

Examine the details on the back of the can for tuna species, fishing method and catch location. There are sustainable options for each of these categories.

The best approach is to opt for skipjack before yellowfin or other tuna varieties. Next, choose tuna caught using “pole-and-line” or “FAD-free purse seine” before “longline” or “purse seine”. Then, check for tuna caught in the Western Central Pacific Ocean – this may appear on the can as FAO Nr. 71. If the can doesn’t at least identify the species or fishing method, it’s probably not worth your time.

2. Consider eco-labels over unverified self-claims

Eco-labels and eco-claims often feature prominently on tuna cans. Eco-labels are market-based tools used to promote sustainable practices. Decoding them can seem challenging, but it doesn’t have to be.

First, it is important to recognise that a dolphin-safe label is not a sustainability label. It focuses only on the impacts of fishing on dolphins. Dolphin-safe doesn’t consider tuna catch levels or other socio-environmental impacts. Most importantly, it doesn’t require independent third-party verification.

In contrast, some newer eco-labels consider a wider set of impacts including target species stock levels, impact on other species and even the social impact on fishers – such as fair pay and work conditions.

So far, MSC is the only label to be recognised by the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative (GSSI), but keep in mind this label is not without criticism.

In recent months, the MSC-certified Pasifical brand has been criticised because its FAD-free purse seine sourced tuna are transported on vessels that can also catch FAD-caught purse seine tuna. Some commentators argue that this enables unsustainable FAD-caught fisheries to continue operating.

On the other hand, MSC has the strongest chain of custody. It can trace every can of tuna from the supermarket shelf all the way back to the fishery. It’s not clear whether the original criticism was driven by competition for supermarket shelf space, as some industry insiders have claimed.

Read more: Here’s why your sustainable tuna is also unsustainable

3. Download seafood guides

Various online guides are also available to help consumers choose sustainable seafood options. These guides rank and recommend seafood using a stoplight system. The recommendations are based on available scientific research or a defined set of criteria.

In Australia, Greenpeace publishes a Canned Tuna Guide that ranks available brands. Australia’s Sustainable Seafood Guide provides recommendations for seafood generally.

Guides are also produced by Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch for the US, Ocean Wise for Canada and WWF’s Fish Forward Project for South Africa and several countries in the EU and Asia.

4. Future technologies, supply chains and transparency

While the steps above assist with making sustainable seafood choices, it doesn’t help if the fish you’re buying has been mislabelled. There is still uncertainty related to transparency and traceability in the supply chain.

To help combat this problem, Coles has partnered with WWF to ensure the seafood it sells is sustainably sourced. Aldi has also introduced an initiative called “Trace Your Tuna” to link tuna to its catch location.

New applications that use tracking data are also developing. Apps are available that scan QR codes and barcodes to provide consumers with extra information about the origins of lots of different products including seafood. These include Oziris in Australia, ThisFish in Canada and the Seafood Traceability System offered by the Korean government.

Simultaneously, new initiatives such as Global Fishing Watch are providing open access to vessel movement data, providing tremendous opportunities for transparency and traceability.

![]() In short, the easiest way to make a sustainable choice when buying canned tuna is to check the contents label and look for a credible eco-label. If you have a little more time, it might be worthwhile to check out seafood recommendation guides or to download a product tracking app on your smartphone.

In short, the easiest way to make a sustainable choice when buying canned tuna is to check the contents label and look for a credible eco-label. If you have a little more time, it might be worthwhile to check out seafood recommendation guides or to download a product tracking app on your smartphone.

Candice Visser, PhD Candidate, University of Wollongong and Quentin Hanich, Associate Professor, University of Wollongong

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/live-migration/www/images/content/groups/public/web/media/documents/mm/uow241372.jpg)