March 13, 2018

Ancient humans flourished through supervolcano eruption

One group of early modern humans thrived through Mount Toba eruption and subsequent global volcanic winter

The eruption of the Mount Toba supervolcano (also known as a caldera) in Sumatra 74,000 years ago was one of Earth’s most explosive volcanic events. It threw a massive amount of ash and dust into the atmosphere, disrupting the climate to the extent that it may have caused a global volcanic winter lasting several years, leading to widespread population crashes and possibly pushing some species – including humans – to the brink of extinction.

However, in a paper published online in Nature this week, researchers show that at least one group of early humans managed to flourish through the period of the eruption and its after effects.

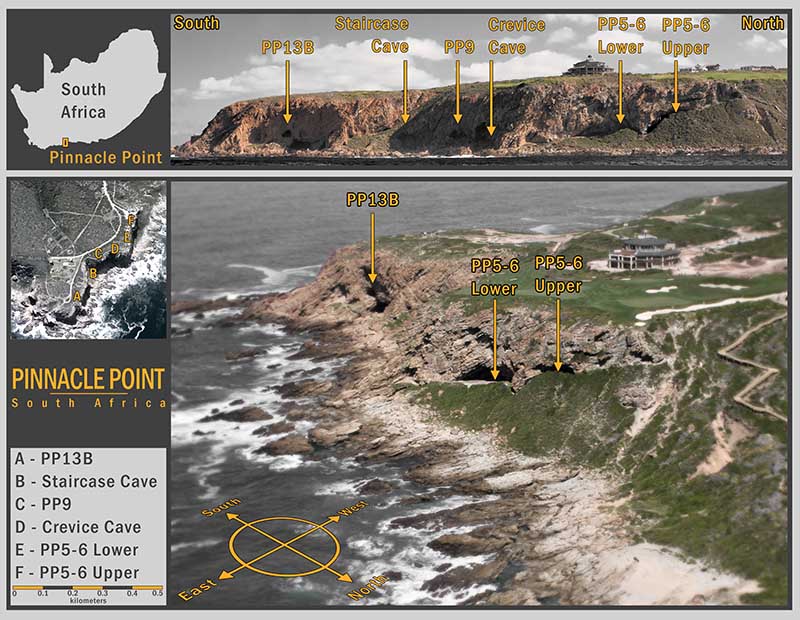

The scientists, including Professor Zenobia Jacobs from the University of Wollongong (UOW), studied two archaeological sites on the southern coast of South Africa – Pinnacle Point and Vleesbaai – that have been dated to around the time of the Toba eruption. There is evidence that people occupied the sites continuously from 90,000 to 50,000 years ago.

Pinnacle Point is a rock shelter and artefacts found there suggest it was a place where people lived, ate, worked and slept. Vleesbaai, about 9 km away, is an open-air activity site where people left stone tools. The same people probably used the two sites.

The Toba eruption propelled an estimated 2800 cubic kilometres of rock and gas into the atmosphere, including microscopic fragments of glass (known as cryptotephra), spreading the debris across the world.

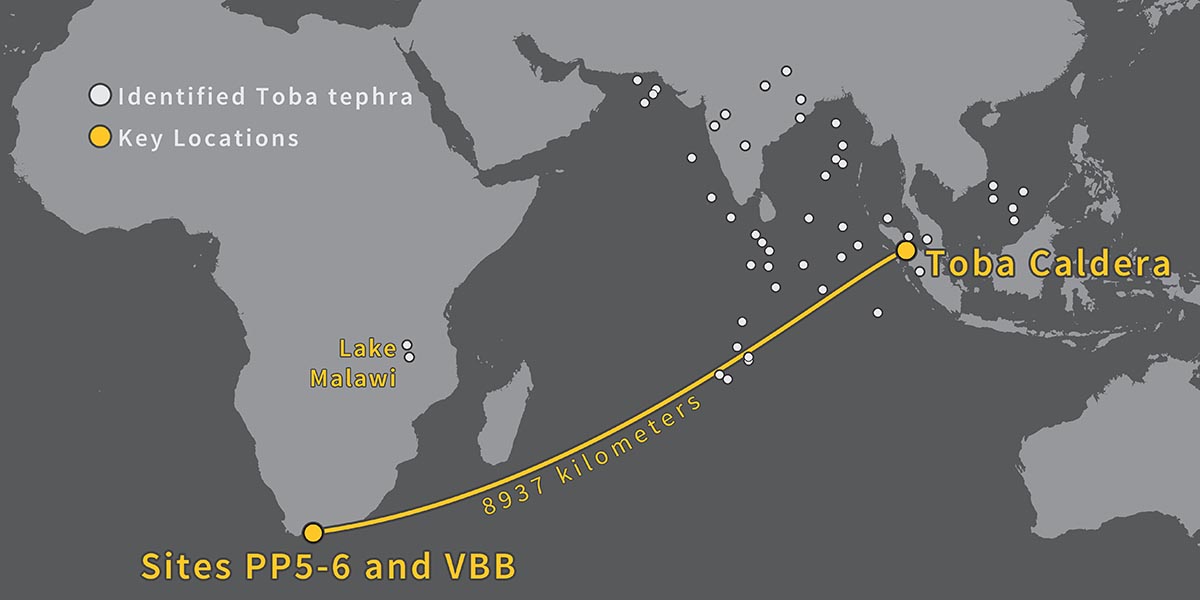

Glass from Toba was found at both Pinnacle Point and Vleesbaai, almost 9,000 kms from the volcano. The glass was identified under the microscope as being cryptotephra. Chemical analysis of the shards then allowed scientists to pinpoint the exact volcanic event from which they originated. Finding the Toba shards confirmed that humans were occupying the sites at the time of the eruption.

Professor Curtis Marean, project director of the site excavations and associate director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, said this meant the researchers could then analyse how those human populations were affected by the event.

“Many previous studies have tried to test the hypothesis that Toba devastated human populations,” he said. “But they have failed because they have been unable to present definitive evidence linking a human occupation to the exact moment of the event.”

The study found that not only did the population on the South African coast survive the Toba event, it actually thrived through that period; the intensity of human activity – as shown by the findings of bones, stone tools and evidence of human fires – increased after the Toba eruption.

The shards at Pinnacle Point were carried nearly 9000 km from the source in Indonesia. Image: Erich Fisher.

The shards at Pinnacle Point were carried nearly 9000 km from the source in Indonesia. Image: Erich Fisher.

In addition to understanding how Toba affected humans in this region, the study has important implications for archaeological dating techniques. Archaeological dates at these age ranges are imprecise, typically giving an age to within several thousand years.

By contrast, the Toba ash-fall was a very quick event in geological terms and has been precisely dated. This meant the location of the shards within the sediment at the sites allowed scientists to test the accuracy of other dating techniques.

Professor Jacobs from UOW’s School of Earth and Environmental Sciences and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage led the dating of the site, using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) to date 90 samples and develop a model of the age of all the layers of the site. OSL dates the last time individual sand grains were exposed to light.

Professor Jacobs said the fact the paper was looking very specifically at how the Toba eruption affected the people living at the time meant the accuracy of the dating became paramount.

“When you pinpoint something and try to answer a very specific question, like did the Toba eruption have an effect on populations, then accuracy becomes really important because you try to tie it to something that is very accurately dated,” she said.

“We started excavating in 2006 and every year, as the archaeologists excavated away more of the layers, I would go back into the field and take a sample from almost every individual layer that we could identify. We’d make sure we knew what the relationship was between the layers, the archaeology, and the sand that we extracted.

“We did that at night because the OSL signal is sensitive to sunlight – we’d go out at night with red torches and extract some sediment with a spoon or a small trowel and put them into a black plastic bag to protect them from light. Then we’d bring it back to the lab and analyse the data.”

Professor Marean said the study lends very strong support to Professor Jacobs’ cutting-edge approach to OSL dating, which she has applied to sites across southern Africa and the world.

“There has been some debate over the accuracy of OSL dating, but Jacobs’ age model dated the layers where we found the Toba shards to about 74,000 years ago – right on the money,” he said.

Professor Jacobs, who dated that layer of the site before the Toba shards were found, said it was gratifying to have the accuracy of her OSL dating methods confirmed.

“OSL dating is the workhorse method for construction of timelines for a large part of our own history. Testing whether the clock ticks at the correct rate is important. So getting this degree of confirmation is pleasing,” Professor Jacobs said.

“I dated those particular layers not knowing there was anything Toba related in there. We first published the ages of that particular part of this site in a paper in 2012 and we dated it to about 70 to 75,000 years ago. It wasn’t until later that year, or even the year after, that the glass shards were identified.”

The research team has been excavating caves at Pinnacle Point, South Africa, for nearly 20 years. Glass shards were discovered at the PP5-6 location. Image: Erich Fisher.

The research team has been excavating caves at Pinnacle Point, South Africa, for nearly 20 years. Glass shards were discovered at the PP5-6 location. Image: Erich Fisher.

The paper concludes by raising the question of whether “the modern human population on the south coast of South Africa was the sole surviving population through a decade or more of volcanic winter, or whether populations elsewhere in Africa thrived through the [Toba] event”.

Professor Jacobs believes it is likely that glass shards from Toba will be discovered at other archaeological sites in Africa rounding out our understanding of how the event affected our ancient ancestors.

“Finding the cryptotephra is almost impossible. The only reason we found them was because of the way we excavated and the way we sampled everything, looking at the sediments under the microscope,” she said.

“If you don't look at these sites to that minute level of resolution then you'll never find these things, but I think more people will start doing that after the results of this study.

“To me, this is a very interesting study from that point of view: just the technical marvel of being able to identify a glass shard 9,000 km away from the source and being able to chemically fingerprint it to say, ‘yes it is from Toba’, and then to date it with different techniques and you get concordance.

“I mean that's fine detailed work as far as archaeological excavations go. Everything at this site was done to the highest level of resolution that you can hope for at an archaeological site.”

The research was funded in part by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project grant.

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/live-migration/www/images/content/groups/public/web/media/documents/mm/uow244433.jpg)