November 12, 2018

Some diseases, like mine, deteriorate rapidly – disability services need to keep up

The NDIS is failing to cater for the changing symptoms and short life expectancy of Australians with rapidly degenerating diseases.

Many people living with the cruel and often rapidly progressing motor neurone disease (MND) are going underfunded during what is likely the most stressful time of their life.

An independent evaluation of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) by researchers at Flinders University found the scheme is failing to take into account the progressive nature and short life expectancy of participants with degenerative diseases.

I’m a molecular biologist and study of the origins of motor neurone disease. I have also had the disease for a little over two years.

Many researchers around the globe are frantically searching for a cure, myself included. But the slow grind of lab-based medical research and the seemingly impossible task of translating this work to positive clinical trials is in stark contrast to the relentless and rapid progression of the disease.

Remind me again, what is MND?

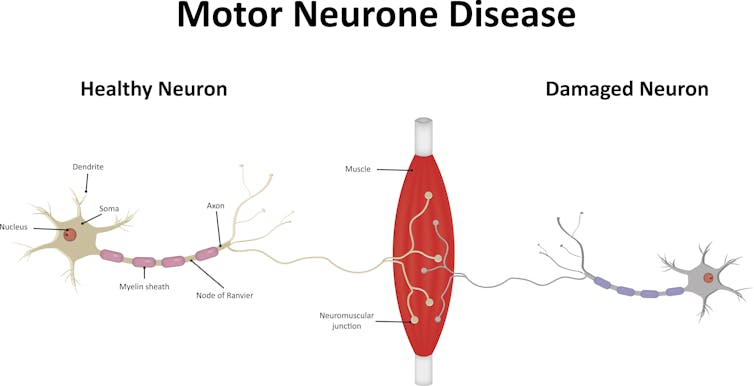

MND is the name given to a group of neurological disorders in which the nerve cells that control the movement of voluntary muscles, known as motor neurons, selectively die.

A progressive paralysis ensues as the muscles of movement, speech, swallowing and breathing no longer have nerves to activate them.

MND affects each person differently, as do the initial symptoms, rate and pattern of progression, and the survival time. The average life expectancy is two to three years from diagnosis but some people with MND can live for up to ten years or longer.

There is currently only one drug approved for use in MND. Sadly, the benefits are modest: studies suggest it may extend life expectancy by three months.

While the hunt for new, more effective drugs goes on, research shows the quality of care a person receives can not only increase quality of life but also increase life span. Access to multidisciplinary care – involving medical, nursing and allied health professionals (physiotherapists, dieticians and occupational therapists) – has been reported to improve both quality of life and survival, by seven to 24 months.

The survival advantage experienced by patients attending a multidisciplinary clinic can be in part explained by access to non-invasive ventilation. Studies have shown that use of a Bi-PAP machine – a small ventilator that helps with breathing – can prolong life by up to 14 months.

But this is only part of the benefit. The increased survival also relates to the complex decision-making processes that occur within a multidisciplinary team and the focus on proactive intervention, and early, holistic care.

This might include, for example, addressing weight loss with dietary supplementation and managing saliva secretions with botox injections, while tracking lung function and neurological changes. Importantly, such care teams also have provisions for rapid access to care when symptoms quickly change.

Quick progression, slow access

The NDIS, for those who have been able to access it, is having a positive, life-changing impact. For me, access to a plan supported my return home from hospital to live with my family. It has allowed me once again to thrive at work.

But my road to approval was not straightforward and the process placed undue stress on my family at an already traumatic period of our lives.

Others with MND continue to experience a protracted planning process and struggle to receive NDIS plans that take their progressing and complex needs into account.

To understand one of the major problems we need to examine the juxtaposition of a slow, cumbersome NDIS approval process with the rapidly progressive nature of MND.

While NDIS plans are usually for 12 months, within a three to six month window of time, it is very possible that a person with MND may progress from being able to walk independently, to needing a powered electric wheelchair.

My rapidly changing needs meant that while waiting for approval for a ramp or lift to access my home, it became unsafe for me to leave the house. Rather than see me house-bound my father-in-law built a ramp from kindly donated materials.

Others are not so fortunate. Another person I know with MND, Mary, has to shower under a hose in the laundry as she continues to wait for approval for bathroom modifications, and Helen fell and broke her spine during her 12-month wait for an electric wheelchair. Sadly, Adrian died before his wheelchair was even delivered.

‘Value for money’

A problem at the core of all MND-related difficulties with the NDIS is that the projected short lifespan of those with MND makes the NDIS baulk at funding high-cost items and modifications.

We are not perceived as being “value for money”. Multiple times during my approval processes, I was asked to prove I was going to live long enough to make a purchase value for money. Other people with MND have had similar experiences.

Decision-making about costs must not come at the expense of the dignity or safety of people living with MND.

There is an urgent need for systemic changes to address the slow and stressful planning process for people with rapidly deteriorating conditions like MND in light of their complex and changing needs and limited life expectancy.

![]()

Justin Yerbury, Research Fellow in molecular genetics of Motor Neurone Disease, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/live-migration/www/images/content/groups/public/web/media/documents/mm/uow253218.jpg)