September 5, 2018

Volatile combination of issues puts junior doctors at high risk of burnout

Study explores triggers affecting doctor physical and mental health

Pressure to perform, lack of support from senior colleagues and inadequate self-care are a volatile combination of factors increasing the risk of burnout and mental health issues among junior doctors.

The physical and mental health of medical professionals has been in the spotlight following a survey published in 2013 by mental health organisation beyondblue that found doctors in Australia have substantially higher rates of psychological distress and attempted suicide than the Australian population.

Doctor burnout not only affects the individual, it can lead to increased absenteeism and depression, medical errors and engaging in risky alcohol use.

Dr Rebekah Hoffman, a practising GP and a PhD student at UOW Graduate Medicine’s General Practice Academic Unit (GPAU), surveyed junior doctors in New South Wales and Victoria to understand the experience of burnout and its causes.

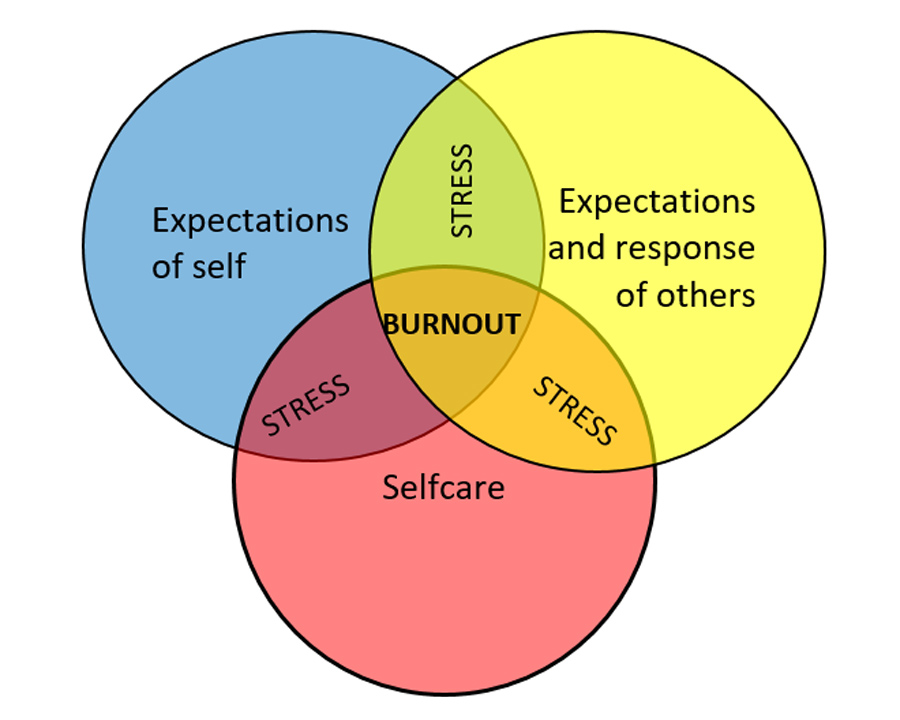

Her study of junior doctors working as general practice registrars and in hospitals found a trifecta of issues that can put a junior doctor at high risk of burnout: they are not supported by senior colleagues, feel they are working beyond their abilities and not looking after themselves adequately.

Two of the factors combining typically leads to high levels of stress. All three combining puts the person at risk of burnout.

A model for risk of burnout in junior doctors, developed by Dr Rebekah Hoffman.

A model for risk of burnout in junior doctors, developed by Dr Rebekah Hoffman.

Dr Hoffman said the typically high-achieving personality types drawn to medicine put additional pressure on themselves to perform even when they know they’re at the limits of their knowledge and experience.

“These are people who have always been at the top of their class at high school and throughout their undergraduate years,” Dr Hoffman said.

“They get into medical school and while it’s humbling to be surrounded by people who are also very talented and striving to do better, it can add to the pressure.

“They build their confidence throughout medical school and when they start their residency or internship the process resets, but they don’t relieve the pressure on themselves to meet their own high expectations.”

While they struggle with their own self-expectations, the long hours and unexpected demands of the placement can increase the risk of burnout.

“There’s good evidence that long hours contribute to stress, with long hours and high patient loads a recurring theme among the junior doctors surveyed,” Dr Hoffman said.

Some survey respondents reported that senior management appeared to lack empathy or were unhelpful when stressed registrars asked for help.

“Some junior doctors felt the senior clinicians had forgotten what the early training years were like. Without support from senior colleagues they really can feel overwhelmed.”

The final and arguably most overlooked area was self-care, or how the junior doctors strived to maintain a healthy work-life balance.

While most surveyed understood the importance of diet, exercise and supportive personal relationships, very few took the step of having their own doctor as part of their strategy to look after themselves.

“Junior doctors need to know it’s ok to look after yourself and to let people know if you’re struggling.” - Dr Rebekah Hoffman

“Junior doctors need to know it’s ok to look after yourself and to let people know if you’re struggling.” - Dr Rebekah Hoffman

The study, ‘Junior doctors, burnout and wellbeing: Understanding the experience of burnout in general practice registrars and hospital equivalents’, was published recently in the Australian Journal of General Practice.

It was co-authored by Professor Andrew Bonney, the Roberta Williams Chair of General Practice at UOW Graduate Medicine.

Dr Hoffman, who experienced burnout in 2013 while working in orthopaedics and now practises as a GP, said she hoped the study would contribute to the important conversation around the health and wellbeing of junior doctors.

Some hospitals have put in place resilience training, and organisations such as the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists have commissioned reviews into guidelines for doctor stress and fatigue.

Dr Hoffman said the measures are good first step, but were incomplete and needed to be supplemented with evidence-based strategies that do not shift blame to the junior doctor.

“If we don't address it, nothing changes. This is an opportunity to introduce new policies and guidelines in doctor training.

“We also need to change the culture of medicine to reduce workloads, to provide learning support in areas where junior doctors don’t feel competent and for senior doctors to advocate for the health and wellbeing of their trainees.

“Junior doctors need to know it’s ok to look after yourself and to let people know if you’re struggling.”

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/live-migration/www/images/content/groups/public/web/media/documents/mm/uow251450.jpg)