March 19, 2019

As home care packages become big business, older people are not getting the personalised support they need

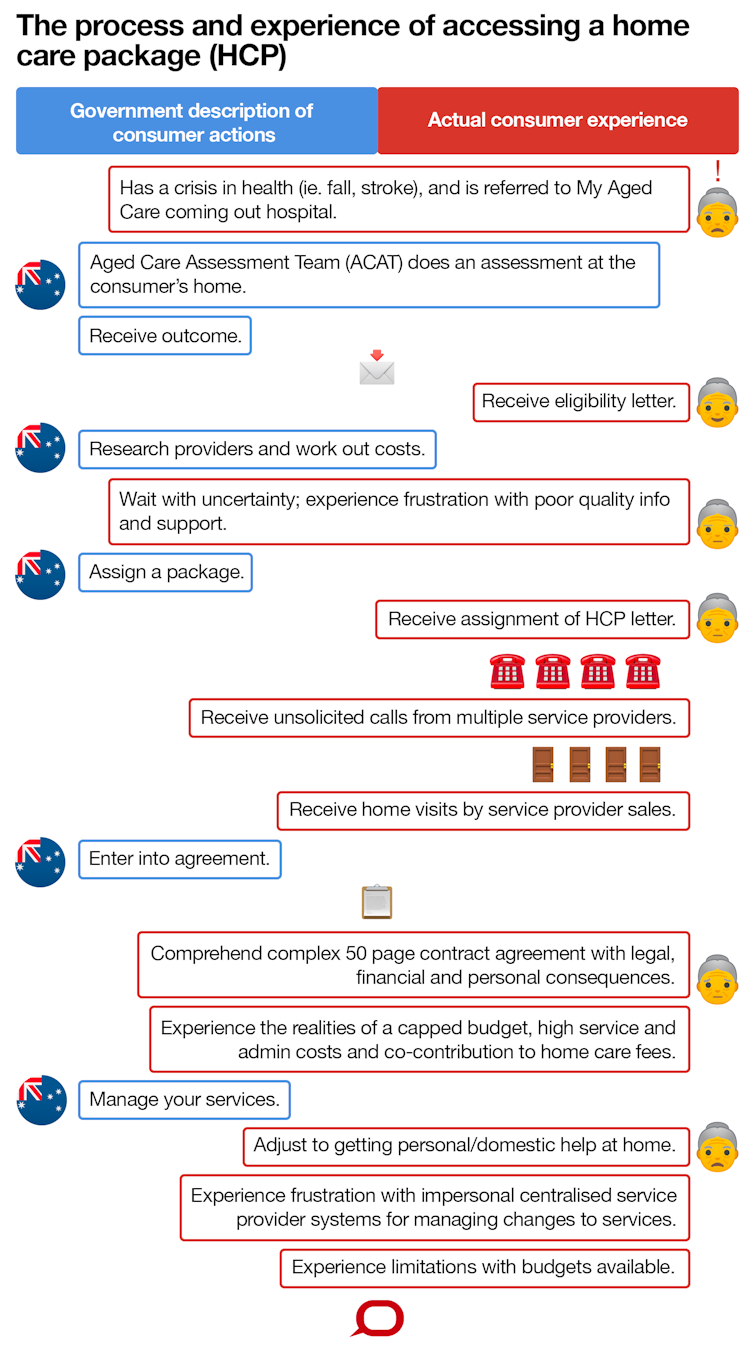

Many older Australians prefer to stay at home than enter residential aged care – but the process of securing home care is riddled with complexities.

The Royal Commission into Aged Care has unleashed a spate of claims of system failure within the residential aged care sector.

Now, as the commission shifts its focus to care in the community, we’re also seeing claims of failure within the home care packages program.

This scheme aims to support older people with complex support needs to stay at home. But what we’ve got is a market-based system where the processes involved in accessing support and managing services are making it difficult for vulnerable older Australians to receive the care they want.

If this system is to be workable, older people need better information and more personalised supports to enable choice and control – especially those with complex needs.

Consumer directed care

A growing number of older Australians are receiving home care subsidised by the government. During the 2017-18 financial year, 116,843 people accessed home care packages.

From July 1 2015, all home care packages have been delivered on what’s called a Consumer Directed Care basis.

This means that, theoretically, home care providers must work with consumers to design and deliver services that meet their goals and care needs, as determined by an Aged Care Assessment Team.

However, in reviewing the active steps outlined in the government pathway to access a package, we must consider the person who is navigating this path.

They are frail older people with complex support needs, often seeking help at times of crisis. These include the growing number of older Australians living with multiple medical conditions and complex age-related syndromes such as dementia.

After a person has been assessed, they will receive a letter informing them they are eligible. However, due to long waiting lists, this does not provide them with immediate access to care; most wait many months before they are actually assigned a package by My Aged Care.

When they eventually receive a letter confirming their package, the consumer will be approached by various service providers. They will need to sign a complex contract with their chosen provider.

If the consumer is feeling frustrated and confused during these early stages, this is only the beginning. The recent marketisation of home care means managing their own care requires going through impersonal, centralised provider systems.

People need clear information to choose a provider

The first thing people assigned a home care package need to do is choose a care provider.

There are now close to 900 different providers offering home care packages. This includes not-for-profits, as well as a growing number of for-profit providers competing for new business.

In reality, however, few older people research different providers. Once they’re assigned a home care package, their name is placed on a centralised database accessible by all registered service providers.

The person then receives unsolicited phone calls from the sales teams of different providers, offering their services and trying to make appointments to come and visit. For consumers, this represents a shift from a familiar government model of care provision to a market model.

Research shows consumers often don’t understand consumer directed care, and this can leave them vulnerable to the forceful marketing tactics employed by some providers. It can also make negotiating a complex contract with legal, financial and personal implications very difficult.

To make informed choices between providers, people need accessible information. There is currently insufficient information for older people and their families to compare services on indicators of quality (such as the number of complaints agencies receive, the training of staff, the types of specialist services they offer, and so on).

To address this gap, the government must commit to collecting and publishing data on home care quality. This would drive service improvement and increase people’s ability to make informed choices between different providers.

Service and administrative fees

To make informed choices, people also need to be able to compare services on the basis of price.

The average profit per client for home care package providers was A$2,832 in 2016-17, but there’s significant variability between providers’ fees.

For example, the use of people’s individual care budgets to cover administration or case management fees ranges between 10-45% of their total package.

High fees and administrative costs may reveal the profit-driven motives of a few unscrupulous providers.

Because of administrative fees, many people are spending a high portion of their individual budgets on case management to support their care.

While there’s evidence case management can provide clinical benefits for older people, in the context of the current home care funding model, it may also leave people with less money for direct care services than they need.

People need support to manage their packages

We’re currently looking at the experiences of people with dementia using home care packages. Unsurprisingly, we’re finding that while they are grateful for the services they’re receiving, they are having a difficult time managing their care. For some this may be due to their limited decision-making capacity, but for many, their choice and control is being limited as much by the service model.

For example, to enable providers to compete in the open market, many have adopted central 1800 numbers to support people to manage their services. This means if consumers want to change something, they are funnelled through this system.

Think about your own experience of service helplines, such as with telephone or energy companies. Now consider a woman with dementia who needs to call a 1800 number to change the time of her shower so she can see her doctor.

Rather than communicating with a local and known case manager, she now needs to speak to someone she doesn’t know and who is not familiar with her care needs.

Instead of facilitating choice and control, this demand on the consumer to constantly articulate their needs to unfamiliar people means many are frustrated, and some are even opting out of services.

How can we improve things?

The three words the government associates with consumer directed home care are choice, control and markets.

But the system doesn’t foster control. Although consumers technically have choices, the marketised and bureaucratic approaches of service providers make it difficult for consumers to articulate and receive support for their personal choices.

The processes, information and supports available to assist older people and their families are inadequate to facilitate the type of choices and control one might associate with “consumer directed” care.

There’s an urgent need to improve the processes for accessing timely home care packages, particularly for those with complex support needs. This includes the quality and accessibility of information, resources and decision-making tools.

There’s also a significant need for training, advocacy and impartial support for choice, particularly for people with limited decision-making capacity, such as those living with dementia.

Research and practice in aged care and disability in other settings provide extensive resources for person-centred planning and decision making which could be adapted for use in our home care system.![]()

Lyn Phillipson, NHMRC-ARC Dementia Development Fellow, University of Wollongong and Louisa Smith, Research Fellow at AHSRI, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/live-migration/www/images/content/groups/public/web/media/documents/mm/uow256977.jpg)