May 16, 2019

Cutting penalty rates was supposed to create jobs. It hasn't, and here's why not

Using a variety of statistical analyses, the authors have found no evidence of more employment in hospitality and retail because of reduced penalty rates.

After three years of submissions, hearings and deliberations, Australia’s workplace relations umpire, the Fair Work Commission, decided in 2017 to decrease the penalty rates paid to retail and hospitality workers on the safety-net award for working on Sundays and public holidays.

For years employer groups had argued that high penalty rates (up to double standard pay) were an unaffordable anachronism in the modern economy, and the commission essentially agreed.

In particular, it concluded the evidence was that cutting penalty rates (by between a quarter and a half) would lead to more trading hours and services on offer on Sundays and public holidays, “and an increase in overall hours worked”.

In other words, reducing penalty rates would create more jobs.

Two years on, with cuts to public holiday penalty rates fully implemented and Sundays partially implemented (being introduced over three to four years) how many extra jobs have been created?

Our research suggests basically none.

What the data tells us

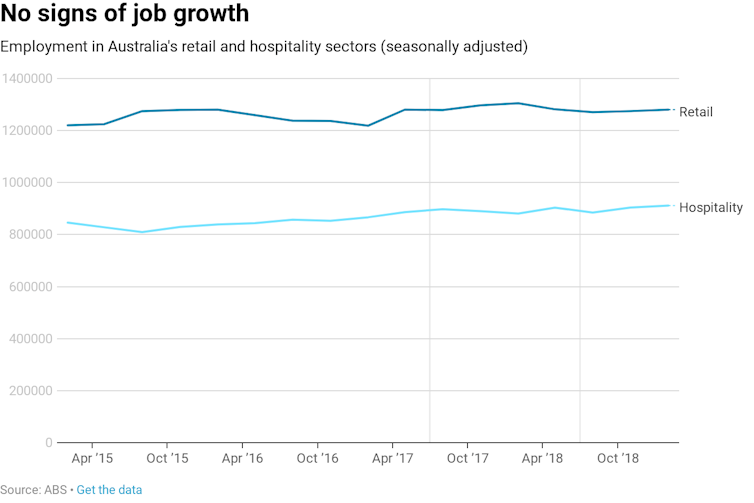

The publicly available data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics doesn’t really help determine the effect of the penalty rate cut. The following graph shows ABS employment date covering the retail and hospitality sectors since 2015.

The key dates are when penalty rate cuts occurred, on July 1, 2017 (full reduction in the public holiday rate and part reduction of the Sunday rate) and July 1, 2018 (further reduction of the Sunday rate).

There is no obvious increase in employment after those two dates, but this doesn’t really tell us the full story. Because the ABS doesn’t collect employment data for Sundays and public holidays specifically. Also the group affected (those on modern award pay and conditions) comprise about a third of employees in these sectors, and they are buried in the stats alongside those on enterprise agreements and individual contracts, whose wages were unaffected by the commission’s decision.

In short, one needs to collect some custom data to do a proper study.

Which is what my colleague Ray Markey at Macquarie University and I did.

In late 2018 we commissioned a survey using a third-party data collection agency. We surveyed more than 1,800 employees and 200 owner-managers in retail and hospitality. We collected data on Sunday, public holiday and weekly employment patterns for modern award employees, as well as those covered by enterprise agreements and individual contracts.

Using a variety of statistical analyses, we were unable to establish any evidence of a relative increase in the prevalence of Sunday, public holiday or weekly employment for modern award employees or employers. Nor could we establish a decrease to the number of hours that owner-managers worked Sunday and public holidays, something else the Fair Work Commission also predicted.

In fact, some of the analysis suggested the Sunday and public holiday employment outcomes were worse for those affected by the penalty cuts compared to those on enterprise agreements and individual contracts.

Flawed evidence

So, why the dud result?

The inescapable conclusion is that the evidence presented to the commission was flawed.

What came from employer groups, trade unions, the Productivity Commission, and expert witnesses (including myself) was indirect and tangential at best, and biased at worst.

No reliable statistical evidence of the effect of penalty rates on employment was presented, either by employers or unions, because no such data had ever been collected.

Of the 151 academic papers the commission referred to in its decision, not one contained sound empirical analysis of the employment impact of penalty rates. It was instead mostly inferred from minimum wage cases.

The evidence in support of penalty rate cuts consisted of employer intentions surveys. One such survey, by an employer group, indicated more than half of its members would employ extra staff if they could cut penalty rates.

One high-profile professor of economics often consulted by employers calculated that reducing penalty rates by 1% would increase employment by 3%. This relied on sources including an unpublished conference paper from 1971 using Danish consumer data and a US study from 1966.

Ultimately, the Fair Work Commission decision was swayed by the Productivity Commission and blind faith in high-school economics – that if the price of labour goes down, the quantity of labour demanded will go up.

But by how much? Don’t ask the Productivity Commission, which admitted it was “difficult to quantify the precise effect”.

Increased minimum wage

At least two factors may have undone the Fair Work Commission’s prediction.

First, some of the savings employers might have made from the penalty rate cuts were nullified by increases in base minimum wage rates.

For example, a retail worker on the General Retail Modern Awardpaid A$50.55 an hour on a public holiday in 2016-17 would get only A$46.98 in 2017-18. But they would have gained 3.3% minimum wage increase. So a full-time employee would be earning A$793.60 a week compared with A$768.20 the previous year.

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry has argued it will take time to see a positive employment impact due to the gradual, phased reduction in Sunday rate cuts. However, the public holiday penalty-rate cut was implemented in full in 2017 and there has been no significant change to public holiday employment.

Yet low-wage growth across the economy

Second, despite relatively generous increases in minimum wages, there has been record low income growth across the economy, while costs associated with housing, energy and food have risen at a rapid rate.

The retail and hospitality sectors depend upon discretionary household spending. It is likely the expected employment stimulus has been affected by a lack of demand and spending in these sectors. Less spare cash after paying important bills means less spending on extra goodies like restaurant meals, holidays, recreational goods – all the things that retail and hospitality rely on.

It doesn’t matter how much you try and reduce business costs via penalty rate cuts, if people aren’t spending money then employers are not going to put extra people on for Sundays and public holidays.

In fact, decreasing the Sunday and public holiday pay for a decent chunk of the labour force may be adding to this lack of consumer demand and confidence.![]()

Martin O'Brien, Lecturer in Economics, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/live-migration/www/images/content/groups/public/web/media/documents/mm/uow258487.jpg)