March 16, 2020

More green, more ‘zzzzz’? Trees may help us sleep

People in neighbourhoods with good tree cover are less likely to suffer from insufficient sleep, a new longitudinal study shows.

Not feeling sharp? Finding it hard to concentrate? About 12-19% of adults in Australia regularly don’t get enough sleep, defined as less than 5.5-6 hours each night. But who’d have thought the amount of tree cover in their neighbourhood could be a factor? Our latest research has found people with ample nearby green space are much more likely to get enough sleep than people in areas with less greenery.

There’s plenty of helpful advice online on sleep, of course. Apart from personal routines, many other things can affect our sleep. Aircraft and traffic noise isn’t helpful. Other environmental factors at play include temperature, artificial light and air pollution.

As a result of these factors and their interactions with others, such as age, occupation and socioeconomic circumstances, the chances of getting a decent night’s kip are unevenly distributed across the population. So it is not simply a matter of personal responsibility and choosing to get more sleep.

Why does green space improve health?

We’ve been studying the health benefits of green space for many years. We recently published research that suggested more green space – and more tree cover in particular – could help reduce levels of cardiometabolic diseases like type 2 diabetes.

Why might green space be good for our health? We hypothesised that parks, woodlands and other nearby green spaces might actually help us to nod off. Green space might counter impacts of noise and air pollution, and cool local heat islands, all of which can make sleep difficult.

These benefits may be especially important in disadvantaged communities where many households might not have air conditioning and underlying health conditions can increase vulnerability.

Contact with nature can also provide opportunities for psychological restoration and stress reduction. It seems the benefits are greatest if there’s more tree canopy and more biodiversity (such as a richer variety of birdlife).

Our early results provided evidence of a link between green space and sleep duration in Australia. Since then, many more studies from various countries have reported similar results.

Importantly, most of this evidence comes from cross-sectional studies – “snapshots” of a point in time. It’s a bit like trying to understand cause and consequence from a single photograph.

In this case, the “chicken and egg” concern with prior evidence is: does green space really support better sleep? Or could it be that people who already get better sleep, perhaps because they have fewer health issues or financial troubles, tend to live in greener neighbourhoods?

What’s new about our study?

Our new longitudinal study addresses this concern. We investigated whether people with more green space within 1.6km had lower odds of developing insufficient sleep over about six years. They did not move home in this time.

We found 13% lower odds of developing insufficient sleep among people in areas where 30% or more of landcover within 1.6km had tree canopy, compared to people in areas with less than 10%. These results were consistent after taking into account factors that can influence both our sleep and access to neighbourhoods with more tree cover. These factors included age, sex, education, work status, marital status and household income.

Our findings help advance the quality of evidence for the influence of green space on sleep, but there’s more to be done. Importantly, some people may have “healthy” sleep durations but still experience disturbed sleep and other sleep quality issues. While our evidence suggests more tree canopy may support healthier sleep duration, our future research will assess whether green space supports better-quality sleep.

Why does the tree canopy-sleep link matter?

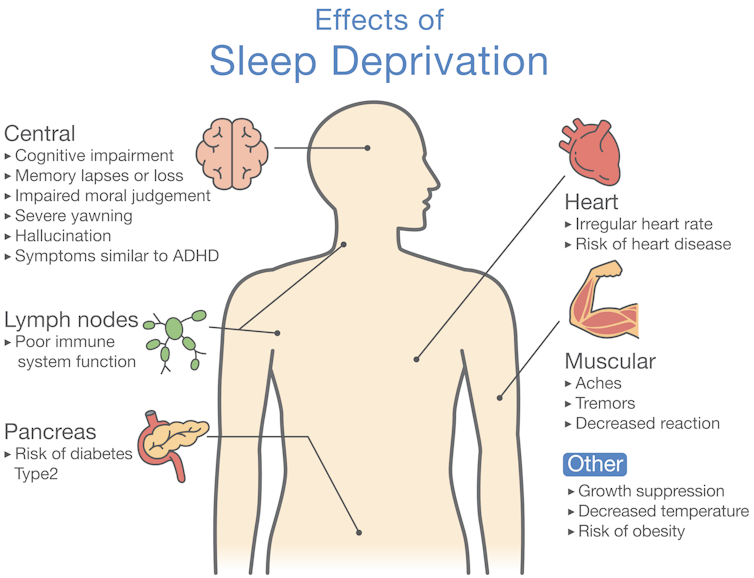

Scientists around the world have found links between insufficient or poor sleep and poorer health, well-being and productivity.

Sleep-related problems affecting four in ten Australians cost an estimated A$40.1 billion in loss of well-being and A$26.2 billion in health system, productivity, informal care and other costs in 2016-17.

So public policies that improve our sleep by (re)shaping the urban environment could have important consequences for societies and economies.

While many people recognise the health benefits of green space, they overlook sleep. For example, the 2018 Inquiry into Sleep Health Awareness in Australia described many factors that influence sleep, but green space was not one of them.

The bottom line

We risk seriously undervaluing green space as an important source of natural capital in our cities if we assume we already know all the ways it benefits health. Some of these assumptions may not stand up to scrutiny. For example, a UK-based study suggests the link between green space and lower diabetes risk might not be increased physical activity.

Some of the biggest health benefits of urban greening policies – such as the New South Wales Premier’s Priorities to increase quality parks and tree cover – might not be the most obvious. Nor can we assume health benefits will effortlessly materialise with more green space. An interesting experimental study in the US concluded use of portable electronic devices while in parks “substantially counteracts the attention-enhancement benefits of green spaces”.

This means how we engage with nature is important in determining how much health benefit we get in return. It highlights the need for equity-focused “nature-based interventions” that enable people to regularly spend more time in urban parks and woodlands, if that’s what they’d like to do.

So there are yet more reasons to get out in the garden, take a restorative stroll in the woods, picnic in the park or rejoice in a botanic garden … and maybe improve your chances of a good night’s sleep!

![]()

Thomas Astell-Burt, Professor of Population Health and Environmental Data Science, NHMRC Boosting Dementia Research Leadership Fellow, University of Wollongong and Xiaoqi Feng, Associate Professor in Urban Health and Environment; NHMRC Career Development Fellow, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/media-centre/Conversation-trees-1920X1080.jpg)