December 15, 2021

That reverse mortgage scheme the government is about to re-announce, how does it work?

The misleadingly named Pension Loans Scheme is available to all retirees with homes and not just pensioners

Many Australians have never heard of the Pension Loans Scheme, and many more assume it’s just for pensioners, which is understandable given its name.

That’s why the government is poised to rename it the Home Equity Access Scheme and make the interest rate it charges more reasonable, in the mid-year budget update on Thursday.

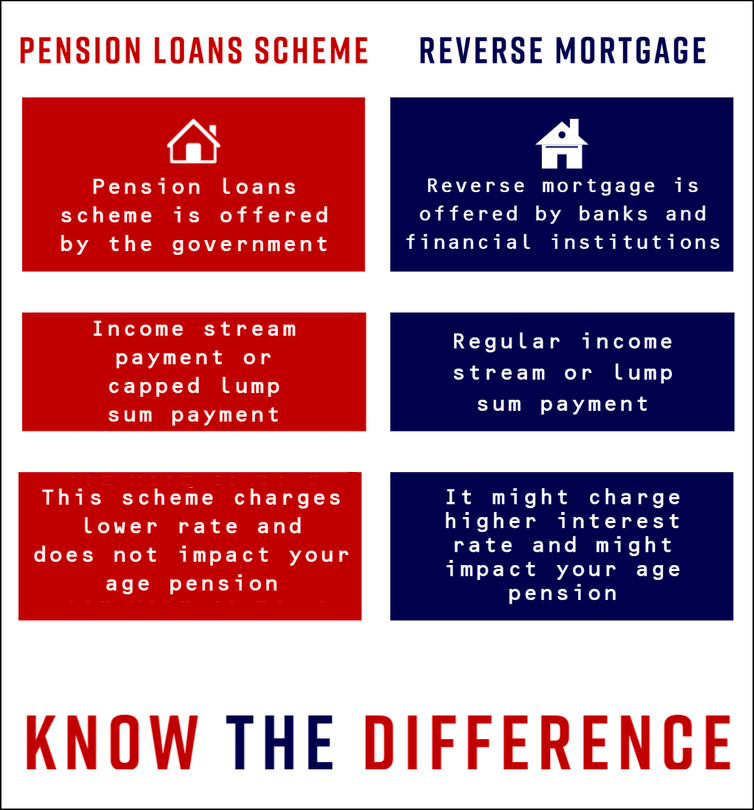

The soon to be renamed scheme is best thought of as a reverse mortgage where instead of paying down a home loan each month, the homeowner borrows more against the home each month, paying off what’s borrowed when the home is eventually sold.

Although reverse mortgages have been provided commercially for some time, the number of providers has shrunk as large banks have left the field in the face of increased scrutiny and compliance costs.

The government version is misleadingly named the Pension Loans Scheme (PLS), even though it is available to all retirees with homes and not just pensioners. It was introduced by the Hawke government in 1985.

The maximum amount that can be made available under the scheme and the age pension combined is 150% of the full pension. This means a retiree who is on the pension can get extra fortnightly payments from the scheme to bring their total payment up to 150% of the full pension.

If the retiree is not on the pension they can get the entire amount of 150% of the pension via the PLS.

The payments stop when the loan balance reaches a ceiling which climbs each year the retiree gets older and climbs with increases in the value of the home.

The ceiling for a 70-year old with a home worth $1,000,000 is $308,000.

The key difference between the PLS and commercial reverse mortgages is that the size of its lump sum payments is limited. Payments under the PLS have no impact on the pension, whereas commercial reverse mortgages can trigger the means test.

As attractive as the PLS might appear, hardly any of the four million or so Australians aged 65 and over have taken it up, perhaps as few as 5,000 – one in every 800.

So in this year’s May budget the government announced two changes to make it more attractive.

One was a “no negative equity guarantee”. Users would never be asked repay more than the value of their property, even if the property fell in value.

The other was the ability to take out up to two lump sums per year totalling up to 50% of the full pension in addition to fortnightly payments.

Total government payments would remain capped at 150% of the pension.

New brand, same scheme

That second change won’t begin until July 1, 2022 and is likely to be re-announced in Thursday’s mid-year budget update.

Also announced in the budget was a decision to raise awareness of the scheme “through improved public messaging and branding” something which is also likely to be re-announced on Thursday along with the new name.

The other change expected on Thursday is a lower interest rate charged on the sums borrowed. In January 2020, the rate was cut from 5.25% to 4.5% in accordance with cuts in other rates. From January next year it should reduce further to 3.95%.

Attractive, but not riskless

There remain risks associated with taking advantage of the scheme.

One is that if you live long enough you are likely to eventually hit the ceiling and be unable to take out any more money, suffering a loss of income.

If you chose to sell your home and move to an aged care service, you need to use a big part of your sale proceedings to pay what’s owed.

Other risks are that neither the interest rate nor home prices are fixed.

Just as the government has cut the rate charged in line with cuts to lower general interest rates, it might well lift it when interest rates climb. And home prices can go down as well as up, meaning that, at worst, all of the value of your home (although no more) can be gobbled up in repayments.![]()

Colin Zhang, Lecturer, Department of Actuarial Studies and Business Analytics, Macquarie University and Ning Wang, Associate Research Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/media-centre/money-jar-Melissa-Walker-Horn-unsplash-499X281.jpg)