What is critical analysis?

Have you ever received the following tutor feedback in relation to the assignments you submitted?

-

-

- “Lack of critical evaluation”

- “Very little critical analysis in this assignment”

- “Not enough analysis of the evidence is taking place in this assignment”

- “Not enough points of view are taken into account”

- “Your work is too descriptive”

-

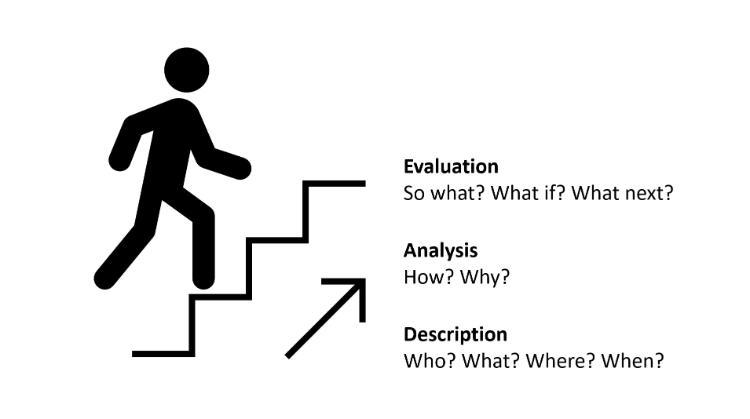

In an academic context, critical thinking is necessary because not all the ideas and theories that you will come across in your research are valid or factual. You will be required to read and investigate many sources, compare and contrast the evidence, and judge the validity or merit of individual arguments in relation to other sources.

This process will help you identify strengths and limitations in the academic arguments presented in the research you accessed. Commenting on these strengths, weaknesses, or limitations in the assignment you write will demonstrate that you are indeed able to think, and write, critically. This process is fundamental in formulating a thesis in relation to the topic you investigate.

Please note: “Being critical” does not necessarily mean that you need to identify issues or problems in the research you accessed.

Being critical involves making judgements or evaluations, challenging assumptions, and/or pointing at the limitations of the research articles you have read. At university, these judgements and evaluations are usually based on evidence gained from reading widely.

Your critical response to research, or an argument in an article, for example, needs to be informed criticism. It needs to be well grounded in research, to demonstrate wide reading, and to consider other evidence. Criticisms in this sense are based on a synthesis of a number of factors, and are not just personal opinion.

When you are engaged in the process of thinking critically about issues, you should be guided by at least the following criteria:

-

-

- Never accept a statement as true merely because someone has said it is true.

- Never condemn a statement as false unless (a) you can produce rational evidence to support your position and (b) you have a sound reason for attempting to demonstrate its falsity.

- Always ask questions of the things you are exploring. For example: “What if? Why? Why not? Who has written this? Is there other research coming to different conclusions?”

-

Critical thinking and critical analysis are integral to academic disciplines and to academia generally because this is the main way that knowledge is added to a field. While academics in a particular field may agree with the conclusions of a particular piece of research, these conclusions may open up other questions which need to be answered.

Only through constantly questioning – “What if? How could? What does this mean for … ?” - is new knowledge added to a field. In this way, academic disciplines constantly evolve.