Subscribe to The Stand

Want more UOW feature stories delivered to your inbox?

:format(jpg)/prod01/channel_3/assets/contributed/magazines/the-stand/2018-08/Lighthouse%5BT4crop%5D.jpg)

Globally, our seas are rising, but what do we stand to lose locally and what if our best defence is already in place?

The United Nations warns that without drastic reductions to carbon emissions and a continuation of business as usual, the planet is on track for three degrees Celsius of warming by the end of the century. Extreme weather events will become more frequent and coastal cities like London, Miami and Shanghai could be inundated.

In Australia, eight out of ten people live within 50 kilometres of the coast and local governments want to be prepared. What do we stand to lose locally to rising seas? And what if our best defence is already in place?

Professor Colin Woodroffe from UOW's School of Earth and Environmental Science is quite matter-of-fact about sea-level rise. Before modern sea-level rise became a critical issue, he studied prehistoric sea level changes, which sculpted broad coastal plains from estuaries in the Northern Territory of Australia.

Using the past as a guide for the future, Professor Woodroffe has become a world-leader on low-lying coastal zones, outlining for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) the vulnerability of our coasts to the impacts of climate change and suggesting ways we can adapt.

"[The issue is] not the pure science of why sea levels are rising, but what we are going to do about it," he says. "Our coasts are dynamic and we can't just say that there will be a bathtub-like change."

"Around Australia, every high-resolution tide gauge is showing a rise of sea level. And we’re not going to reverse it."

- Professor Colin Woodroffe

He carefully explains the local variations we see to the global average sea-level rise. Broadly, as oceans heat up the water expands, pushing sea levels higher. Warmer waters melt ice shelves in Antarctica and Greenland from the bottom up, accelerating sea-level rise globally.

As this grounded ice disappears, the Earth's crust tilts like a see-saw ever so slightly on the viscous mantle beneath. But Professor Woodroffe is unequivocal about our future.

"Around Australia, every high-resolution tide gauge is showing a rise of sea level. And we're not going to reverse it," he says. "Even if we stopped emissions tomorrow, there is already so much energy in the system, so much heat in the oceans, that we're already committed to sea-level rise beyond 2100."

Professor Colin Woodroffe

A review of evidence in a report by the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer in 2009 concluded that planning benchmarks representing sea-level rises along the NSW coast of up to 40 centimetres by 2050 and up to 90 centimetres by 2100, relative to 1990 levels, were sound projections.

The records are stacking up. In Sydney Harbour, the Fort Denison tide gauge has been measuring sea level since 1886, the longest record in Australia. Sea levels peaked during the 1974 storms but levels in December 2017 and January 2018 have nudged that record.

"We're talking a hundred-year record [and then some] and yet the fourth and the fifth highest water levels were recorded during completely separate events in the last six months. Whatever debates remain, observations of sea level rise are the least disputable," Professor Woodroffe says.

Despite moving goal posts with each change in state government, local councils have prepared coastal management plans to outline the risk of beach and cliff erosion, shoreline recession and coastal inundation in their area. These natural processes are exacerbated by climate change.

"It's been a long time coming, but what we need is exactly what we're seeing with a report like this: mapping out those areas that appear vulnerable and most subject to erosion and inundation," Professor Woodroffe says.

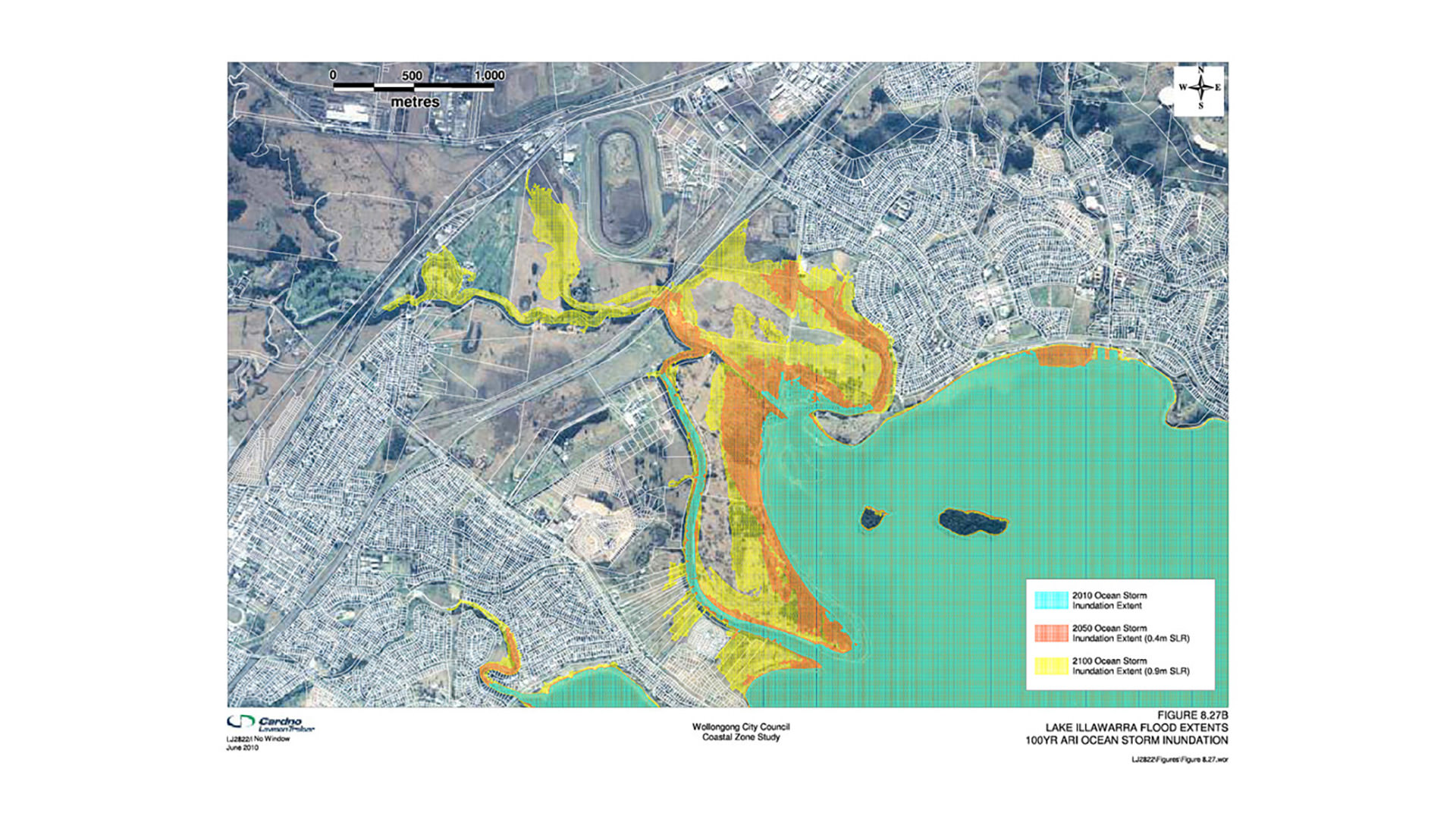

Looking towards 2100, Wollongong City Council has named a number of buildings in its plan, including WIN Stadium at City Beach, recognising that this infrastructure is highly likely to be impacted as seas rise and storms surge. Ocean pools, cycleways and boat harbours are also on their list. Lines drawn to highlight residential properties at risk are likewise causing concern in the community.

A map from the council's Costal Zone Study showing how ocean storm inundation will change over time

When we think of sea levels rising gradually -the high-resolution tide gauge at Port Kembla shows sea levels creeping up by three millimetres per year, on par with the global average - it might be hard to imagine the damage inflicted.

But as the planet warms, extreme weather events will become more frequent and intense: a major flooding event that would typically strike Sydney once a century is likely to occur every month or so by 2100. As sea levels rise, the highest tides will be higher, Woodroffe explains, and rainfall won't drain from the escarpment as effectively as it would have when the water level was lower.

Put together, when a severe storm coincides with a high tide on an even higher sea, our beaches will be hit hard. "But the shoreline is very dynamic," Professor Woodroffe says, describing the natural phases of beach erosion and sand dune recovery.

Professor Woodroffe cites the East Coast low of June 2016. The storm lashed the east coast of Australia from Central Queensland to Tasmania. It ripped out walls of the Coogee Surf Club in Sydney and wreaked havoc in the Illawarra.

"We had quite dramatic inundation locally. That storm coincided with one of the highest tides," he explains. "The reoccurrence of these unusually large events and what the effect will be when the sea is slightly higher needs to be taken into consideration."

Local councils have heeded that warning, prioritising actions to protect public assets and residential properties in their plans. They've also recognised that with rising sea levels and increasing rainfall, estuaries will overflow.

"Many of the impacts of sea level rise are going to occur in estuaries, more so than on the coast," explains Professor Woodroffe. "We'll see subtle inundation of our estuaries and creeks, the so-called Venice effect, and experience a lot more nuisance flooding." Parts of Thirroul and Towradgi are likely to be affected in this way.

Undoubtedly, estuaries are under threat but they have their ways of coping with change. Their vegetation creates a natural barrier that can help mitigate the risk of sea-level rise - and it's already in place.

Australia has the third most extensive mangroves after Indonesia and Brazil. Most are in the tropics but locally, mangroves line the Shoalhaven and Minnamurra River estuaries where these rivers meet the sea.

UOW Ecologist Associate Professor Kerrylee Rogers thinks mangroves are underrated and undervalued. "They're often seen as a blight on the landscape, but they've got incredible capacity to adapt and adjust, which we don't account for very well," she says.

Salt-tolerant mangroves reside in a fluid intertidal zone and create a cosy habitat for fish and crustaceans beneath the surface, shorebirds and bats above. They litter the ground with detritus leaves that break down and sustain a web of microorganisms.

"Mangroves are a natural defence and probably the best response we could have to sea-level rise."

- Associate Professor Kerrylee Rogers

Standing together, mangroves also offer protection against storms and erosion. Their arching roots anchor sediment that has been pushed down river or swept in on the tide. As it accumulates and mangroves deposit their own organic matter below ground, these plants build elevation and can adjust to rising seas.

"Allowing them to do that rather than removing them from the landscape, or armouring the shoreline, adds a buffer to any community behind," Professor Rogers explains. "It's a natural defence and probably the best response we could have [to sea-level rise]."

Increasingly, their ability to sequester carbon is being recognised.

"Mangroves pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into their biomass, locking it away in root material," Professor Rogers adds. The more wetlands we have, the more carbon is locked up underground.

UOW Ecologist Associate Professor Kerrylee Rogers

For more than a decade, Professor Rogers has been surveying mangroves and salt marsh at different sites to characterise the vulnerability of our local estuaries to climate change. With a team of students, she has studied the Shoalhaven and Minnamurra estuaries closely, and further afield, the Hunter River estuary that frames Newcastle.

Where Professor Woodroffe used to tramp through soggy sediments, Professor Rogers conducts surveys using LiDAR, an airborne laser that traces the shape of the earth's surface and measure its ups and downs. She combines this information with traditional sediment cores and satellite images to measure carbon accretion and their response to sea-level rise.

"How and where the sediment gets deposited is different in every estuary - and so is how they will change. That's why you need to look locally," she says.

The low-lying farms surrounding the Shoalhaven River are particularly vulnerable to flooding, she says, but plenty of sediment is funnelled down the catchment, which means mangroves can build elevation as sea levels rise.

"The intertidal zone is bigger and there's a lot of capacity to adapt," Professor Rogers explains. "That's almost the opposite for Lake Illawarra. It's a large body of water but it has less sediment supply, a smaller intertidal zone and significantly less capacity to build elevation."

Because of this and community debate about what to do about the lake, Lake Illawarra has its own management plan. Sea walls built to open the lake entrance - now threatened by rising seas - have completely changed the hydrodynamic behaviour of the estuary, Professor Rogers says.

"People wanted to control the coastal processes but when we change how an estuary behaves, it becomes more unpredictable."

Mangroves have been moving upslope, encroaching on their wetland neighbours, the salt marsh, for decades in southeast Australia. One explanation is that mangroves are being pushed landward by rising seas.

Wetlands have coped with past sea-level changes in the same way, the mangroves moving with the tides. "We can learn something from that and try to model what will happen to them," Professor Woodroffe says. "The hard bit is modelling what humans are going to do."

Place a building, seawall or flood levee on the shoreline and it changes the natural processes. Mangroves suddenly have no room to move. If sediment supply is restricted as well, they can't build elevation. Wetlands get squeezed between the rising water and a wall, and we risk losing our best carbon sinks.

"It depends whether urban environments have the space to let mangroves expand," Professor Woodroffe says.

Associate Professor Kerrylee Rogers believes we need to take a local approach to rising sea levels

Professor Rogers agrees. "It comes down to how people perceive the landscape, how people want it to appear, to behave and to be."

Elsewhere in the world, communities are choosing to fortify the shoreline but in the case of New Jersey, USA, Hurricane Sandy obliterated everything. "They want to control the landscape," Professor Rogers says. "It's not something we do here. We don't develop our shoreline quite like that."

"In the Illawarra, because the mountains are so close to sea, we've got this narrow coastal plain and we get these unique little estuaries - and they're quite ready to defend themselves."

If we value our wetlands.