Appease, submit or resist

Luis Gómez Romero on human rights, decency and the law in the age of Trump.

March 9, 2017

Luis Gómez Romero on human rights, decency and the law in the age of Trump.

While the problems of Mexico and its relationship with United States President Donald Trump might seem a long way away and very different to those of Australia, legal scholar Luis Gómez Romero argues it is vital for Australians to understand what is happening there.

The way the Trump administration behaves towards its southern neighbour, he says, is the template for how the US will treat other countries, including Australia.

"The world now has three options in how to deal with Trump: appease, submit or resist," Gómez Romero says. "History and geography have made Mexico the first line of resistance and that's why it's important to inform the Australian public about what is happening there.

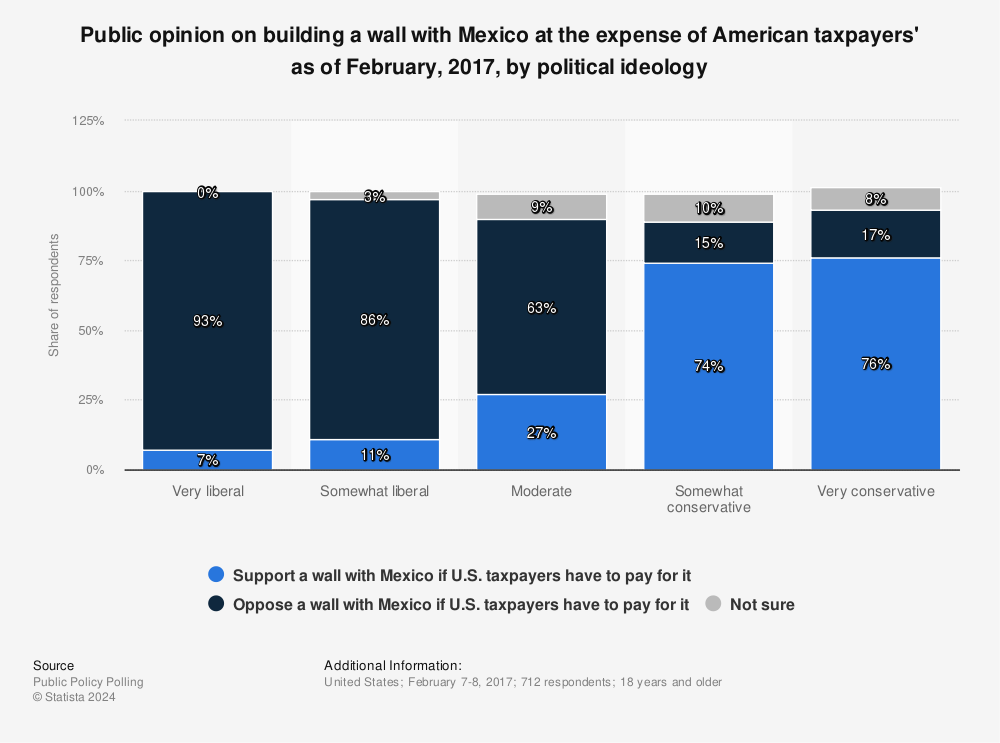

"For example, in recent years Mexican immigration to the United States has actually dropped. This idea that there is an invasion of people with moustaches and sombreros - it's false. Migration is falling.

"The government of the United States is treating Australia horribly - the way in which the President backed away from the Trans Pacific Partnership and the way he dealt with the Australian Prime Minister in that famous phone call."

Dr Luis Gómez Romero. Photo: Paul Jones

An immigrant himself, Gómez Romero has just one quibble with the citizens of his adopted homeland, and it is with their lack of political engagement.

"I like the people here. Australians are an easy-going people with a good sense of humour," he says. "The only thing - and this is part of my commitment as an academic - is that there is a bit of complacency towards politics.

"With a more active public, things would be significantly improved. That's what democracy actually used to mean - to be involved, to be engaged, and not to let politicians, judges, bureaucrats manage the public sphere. The citizens need to have a say as well."

A senior lecturer in Human Rights, Constitutional Law and Legal Theory at the University of Wollongong, Gomez Romero migrated to Australia in 2013. While Wollongong is a very different place to Mexico City, where Gómez Romero grew up, he is so enamoured of his new home he plans to live the rest of his life here.

"I grew up in Mexico City. It's a huge city, the last time I looked at the census it was 25 million people, so the population of Australia in one city," Gómez Romero says. "Where there are 25 million people it creates problems - just even the math of going from one side to the other and the traffic jams. It's also a very interesting city with a vibrant, cultural and intellectual life.

"But I'd rather live in Wollongong, which also has a rich cultural and intellectual life. You have the beach, the mountains, it's a beautiful part of the world to live in."

"Mexican immigration to the United States has actually dropped. This idea that there is an invasion of people with moustaches and sombreros – it’s false." - Luis Gómez Romero

If you've read any of Gómez Romero's many essays in The Conversation - he has been writing prolifically on issues of Mexican-US relations since Donald Trump's election to the United States presidency on November 8 - you'll know that he himself is deeply engaged in the political debate, particularly where it intersects with law, human rights and common decency.

While the Trump campaign and presidency have put Mexico into the media spotlight, his articles give us a perspective on United States-Mexican relations that is too rarely seen in Australia - the view from the southern side of the Rio Grande.

And when you consider that perspective, it quickly becomes apparent that for all President Trump's tweets about "bad hombres", "big beautiful walls" and jobs being exported south of the border, it is Mexico that has suffered more in this relationship than the US.

We MUST have strong borders and stop illegal immigration. Without that we do not have a country. Also, Mexico is killing U.S. on trade. WIN!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 30, 2015

"On November 8 I was quite shocked about what was happening in the United States," he says. "I was talking with my daughter - she is 5 years old - and she asked, 'why are you so sad?'

"I told her there is this person who will now have huge power who has laughed at people with disabilities, who has said horrible things about women, who thinks Mexicans are essentially evil, and so the people we love back in Mexico are facing very challenging times.

"She told me, 'well, he can say Mexicans are evil but he's a liar because he doesn't know me'.

"I said, 'well, why do you say he's a liar?', and she told me, 'he can't tell that all Mexicans are evil if he doesn't know me. He has to know all Mexicans to say they are evil'.

"I said, 'well, that's actually a sound moral argument'. Then I felt I had to do something about it so I have been writing again about these subjects: migration, drug policy in Latin America …"

Mexico, Madrid, Montreal ... Wollongong

It was a sense of outrage at the injustice he saw around him as a schoolboy in Mexico City that inspired Gómez Romero to study law. "Inequality is a characteristic trait of Latin American," he says. "As a teenager I was concerned about inequality and decided I had to do something about it."

Although his interest now lies on the academic side of law, initially he saw law as a pathway into politics. After completing his law degree he worked for time as policy advisor for President Vincente Fox's Conservative National Action Party government, which came to power in December 2000 after 71 years of one-party rule in Mexico by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

"The party wasn't too appealing for me but it was the chance after 70 years of an authoritarian regime to participate in the movement of Mexico towards democracy and I found that appealing." Gómez Romero says. "I was an advisor for the transitional government and later an advisor for the Ministry of Labour."

Dr Luis Gómez Romero wants people to be more engaged in political discussion. Photo: Paul Jones

That brief stint was enough for Gómez Romero who says he has no interest in working in government again.

"My experience in government was a little disappointing," he says. "After 70 years of authoritarian regime I was expecting a politics more committed to principal, to freedom, to equality, to accountability. But things in the government work more slowly. The work I do here at the university is more important in terms of educating the public and discussing ideas openly. And I love teaching! It's one of the joys of my job."

Gómez Romero's journey from political advisor in Mexico City to law lecturer in Wollongong was a circuitous one that took him first to Spain, where in 2009 he received his PhD in Jurisprudence at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, and then to Montreal, Canada, where he had a fellowship at the Institute for the Public Life of Arts and Ideas (IPLAI) at McGill University.

On the advice of his supervisor at McGill, Professor Desmond Manderson, founding director of the Australian National University's Centre for Law, Arts, and the Humanities, Gómez Romero decided to pursue his career in Australia, joining the UOW School of Law in June 2013.

Harry Potter and the Advocate for Human Rights

While Gómez Romero has found his calling in academia, that does not mean he has disengaged from the outside world of politics and society. Indeed, his academic interest lies in how the law operates in the real world, how it interacts with politics, society and culture.

One area he is particularly interested in is normative approaches to law; that is, looking at the explicit or implicit moral reasoning behind laws.

The special issue of Law Text Culture on the law in comics co-edited by Gomez Romero.

For example, is it a just law? Does it oppress or disadvantage anyone? Does it make the world a better place?

Popular culture offers a good way in to normative arguments as it shapes people's ideas about law and justice. Gómez Romero's PhD dissertation was on "Fantasy, Dystopia and Justice: Harry Potter's saga as an Instrument for Teaching Human Rights".

He also co-edited an issue of the journal Law Text Culture that addressed comics as a source of legal theory and legal ideology.

"The law is more than what we see in the statutes, regulations, court decisions - that's just the surface, like the top of an iceberg.

"When a student arrives here in first year they already have a vernacular concept of law that has been structured through years of consuming popular culture - that is the part of ice that is below the water and was there long before they arrived at law school.

"When I talk with my friends in Mexico they may not know theories of law, but they know Harry Potter and we discuss the issues of justice that are embedded in the magical world of Harry Potter - for example mental disabilities, werewolves, and the discrimination the werewolves suffer within this world."

And to get more people involved in the debate about how laws are made and legal decisions arrived at, the first step is getting them thinking about legal issues and feeling they have the right to voice an opinion about them.

One landmark decision he would like to get Australians thinking more about is the High Court's ruling last year that the offshore detention of asylum seekers was constitutionally valid (Plaintiff M68/2015 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2016], High Court of Australia).

I will end illegal immigration and protect our borders! We need to MAKE AMERICA SAFE & GREAT AGAIN! #Trump2016https://t.co/wd3LlMz01I

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 13, 2016

"Australian people can make the High Court judges accountable for what they have ruled by learning about the content of the decision and criticising it," Gómez Romero says. "The judiciary needs its sphere of independence, but when judges make a decision they also have to persuade us about the correctness of their reasoning and then citizens, if they know what has been decided, can criticise the decision.

"They can push their representatives to enact legislation in order to make unjust decisions obsolete. It's an example of how the engagement of the public with politics in the broadest sense of the term would be good I think for Australia.

"Another High Court decision Gómez Romero says needs criticising is 1998's Kartinyeri versus Commonwealth (about the Hindmarsh Island bridge controversy) in which the court ruled that the race powers in the constitution provide Parliament with the power to enact laws that are detrimental to a specific race.

At a time when the rest of the Western world was debating the extent to which affirmative action should be accepted - that is, discriminating positively in favour of groups that had suffered historically from discrimination against it - the High Court of Australia decided that the constitution allowed for negative discrimination.

"That's what the Australian Constitution says because the court has defined this power of the Parliament in this way, so it means Parliament has the power to enact racist laws," Gómez Romero says.

"I find that deeply disturbing. It needs to be discussed. The decision needs to be criticised. The judges that decided this need to be held accountable for the decision and held accountable by public opinion. The public needs to assess the decision, criticise it, and then demand of their representatives in Parliament: 'Let's change this'."

The path of most resistance

If Gómez Romero, can see any silver lining in the storm clouds of the Trump Presidency it is in the energetic response his election has provoked from those opposed to his policies and rhetoric. Whatever you think of Trump, he has certainly got people engaged in politics again.

"The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek famously said just before the election that he would prefer to see Trump win because he is going to shake things up, he is going to prompt a resistance," Gómez Romero says.

"I would never say that because it's one thing to think of yourself in your ivory tower observing the world and thinking 'oh, let's see what happens … ', but on the other hand you are a human being living your small life and you don't want everything to crumble around you.

"But let's take it in a positive way; it is commonplace to say that from problems opportunities can arise, so this can be a chance to have a more decent world. And Mexico, because of history and geography, is now in the frontline and can give an example of decency to the rest of the world regarding its own policy towards Central American migrants. In order to claim decency from the United States, Mexico needs to be decent itself.

"The world now has three options in how to deal with Trump: appease, submit or resist. History and geography have made Mexico the first line of resistance." - Luis Gómez Romero

"Mexico is playing this sad role in the migration policy of the United States, by basically pushing the border of the US south to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec - the narrowest part of Mexico - through an agreement the Peña Nieto administration reached with the Obama administration to deter migrants from Central America from travelling through Mexico to the US. Now that Trump has removed all these agreements ... the Mexican government has a chance to be decent to migrants from Central America."

And when governments fall short it is up to individuals to rise to the challenge.

"The fact that governments are not decent does not prevent people from being decent," Gómez Romero says. "Even if you are a conservative, you have to keep institutions alive that enable you, whatever your ideology, to have some voice … and the way to do it is to be strong and to own your own heart and own your own head.

"If you don't speak your mind because you are afraid, if you let a bully destroy these institutions, then you will not have a chance. And you are destroying the chances for everyone in the future.

"In the play Mariana Pineda, by Federico García Lorca, a man who is in love with Mariana Pineda tells her, '¿Cómo darte este firme corazón si no es mío?': 'How can I give you my strong heart if it doesn't belong to me?'

"So the way to face these challenges, to face these dark times is to keep that in mind; we have to own our hearts, we have to own our minds because otherwise how am I going to give my heart to my daughter, to my wife, to my students, if it doesn't belong to me?"